Wire has been a consistent presence on the playlist of late, particularly albums made since Object 47, the first recording after the departure of Bruce Gilbert, was released in 2008.

While there have been lots of commentary on how many late-period Wire albums just don't measure up to the groundbreaking, innovative work of early classics like Pink Flag or Chairs Missing, those remarks seem inherently unfair.

This is especially true because, how many bands that came up in the late Seventies when Wire did, are even still around, much less regularly releasing new material of consistent high quality, as opposed to, say, running around the reunion and revival circuit rehashing the greatest hits from days of yore?

Having not heard Wire until 1987 probably precludes obsessive comparisons between recent material and the early recordings that inspire so much nostalgia, much of it understandable. Still, how about looking at the later-period albums on the merits.

Given the above, Object 47 was, after the abrasive and bracing blast that was the remarkable Send (2004) including a Los Angeles performance at a small venue that was blisteringly loud, a reflection of how the three-piece without Gilbert could carry on and make excellent music that carries the spirit of Wire forward.

"One of Us" is one of many Wire tunes that, in a more equitable but likely improbable world, would be a hit. It has a fine Graham Lewis' bass riff, an anthemic chorus, an excellent Colin Newman vocal, and Robert Grey's metronomic drumming holding the piece tightly together.

In fact, the album's sequencing is very strong with "Mekon Headman" (mistaken by some as an attack on the cult band, The Mekons) and "Perspex Icon" being other highlights. "Hard Currency" has a hypnotic bass line and some fine stop-time breaks along with Grey's cymbals as the main rhythmic guide. The finale, "All Fours" has a growling guitar riff with the bass and drums in a propulsive synchronicity under which is maybe Newman's best vocal on the album. Page Hamilton's "feedback storm" adds a welcome measure of extra tension and texture. It was a great way to end an excellent and reaffirming recording.

So, whatever the comparisons to the "good old days" might be, Object 47 was proof positive that Wire without Gilbert was not only viable, but capable of great artistic relevance and development. Things just got better with such recordings as Change Becomes Us, Red Barked Trees and subsquent albums, especially Wire.

No criticism, no reviews, no file sharing, just appreciation, on the basic premise that music is organized sound and from there comes a journey through one listener's library. Thanks for stopping in and hope you enjoy!

Sunday, September 29, 2019

Friday, September 27, 2019

King Crimson: Radical Action to Unseat the Hold of Monkey Mind

A few weeks ago was the fourth time seeing King Crimson, the first in 1984 at the Greek Theatre with the quartet of Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew, Tony Levin and Bill Bruford at the end of the tour that was followed by the termination of that phase of Crimson. At eighteen, I had no interest in seeing a "prog" band when I was first asked to go, but the friend who asked loaned me several albums from In the Court of the Crimson King to Starless and Bible Black and on to Discipline and it was the latter 1981 classic that convinced me to go.

The concert was amazing for so many reasons, including the interlocking guitars of Fripp and Belew, the latter's songcraft and easy stage banter, Levin's prowess on the bass and Chapman stick, and Bruford's superlative drumming. When Crimson splintered, though, I ended my budding interest in the band (buying the Vroom EP in 1994 did not stir enough to rekindle the desire to pick up the thread) and that lasted all the way to 2009.

At the time, KC had just gone through a short tour the prior year and plans for a 40th anniversary tour were aborted due to scheduling (and, likely, other) conflicts. Fripp then went through a series of lawsuits over royalties and other issues, worked on a book that apparently has been shelved, and stated he'd never tour again.

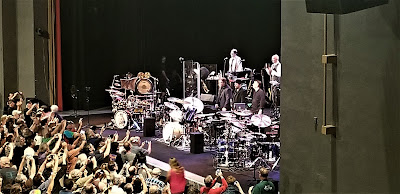

Suddenly, in 2013, that all changed, and a new concept for Crimson was formulated by Fripp, including a front-line trio of drummers, the return after forty years of the amazing Mel Collins on flute and saxes, the always-reliable Levin, and the introduction of Jakko Jakszyk on vocals and guitar.

In 2014, the band came to Los Angeles and played the beautiful old Orpheum Theatre and, after thirty years, it was quite a sight to see Crimson again. The first half-hour, though, was a challenge trying to acclimate to the massive wall of sound created by drummers Pat Mastellotto, Bill Rieflin and Gavin Harrison. All of them are fantastic at their instrument, but it did take that time to adjust to hearing the din and, probably, they were still working out the dynamics of playing together.

In 2017, the band was back, though were now four drummers with the addition of the unknown Jeremy Stacy and he and Rieflin also played keyboards. The June show at the Greek was also very enjoyable and the band played really well.

BUT, the seven-piece (Rieflin sat out this tour) that walked onto the stage at the Greek on Tuesday sounded miles ahead of that excellent ensemble and it was the trio of drummers who really propelled the band forward in what can only be described as a powerful, thrilling and stunning performance by a thoroughly road-tested and stage-hardened juggernaut.

The truth is that everyone played great. Mel Collins was fantastic on his various saxes and flutes and even threw in bits of old tunes like "Tequila" to build the fun that isn't always associated with the band. Levin is always awesome, providing just the right amount of low end to hold everything together, including playing with three monster drummers. Jakszyk was in top vocal form and seemed much more comfortable with tunes associated with great vocalists like the late Greg Lake and John Wetton as well as Belew.

As for Fripp, it is abundantly clear that he is vastly more energized and playing with far more enjoyment with this group than at any time. As with earlier shows, his guitar may have been given a little less volume than it could be, but his playing demonstrates the enthusiasm of working with an ensemble at its peak level of performance.

The Radical Action to Unseat the Hold of Monkey Mind box set includes three CDs of live performances from 2015, with discs devoted to "Mainly Metal," "Easy Money Shots," and "Crimson Classics" and shows the band gelling to the degree that the type of telepathic interplay, between the three drummers and the ensemble generally, was becoming institutionalized, but not in a robotic rote way.

The added benefit are three discs (one Blu-Ray and two standard DVDs) of videos of live performances, so that the ensemble can be seen as well as heard generating the reworking of so much classic material, along with some newer pieces.

Who knows whether this 50th anniversary tour means in terms of the future of King Crimson, but the concert was remarkable and this longest-lasting incarnation seems primed to keep going and audiences are there to support it.

The concert was amazing for so many reasons, including the interlocking guitars of Fripp and Belew, the latter's songcraft and easy stage banter, Levin's prowess on the bass and Chapman stick, and Bruford's superlative drumming. When Crimson splintered, though, I ended my budding interest in the band (buying the Vroom EP in 1994 did not stir enough to rekindle the desire to pick up the thread) and that lasted all the way to 2009.

At the time, KC had just gone through a short tour the prior year and plans for a 40th anniversary tour were aborted due to scheduling (and, likely, other) conflicts. Fripp then went through a series of lawsuits over royalties and other issues, worked on a book that apparently has been shelved, and stated he'd never tour again.

Suddenly, in 2013, that all changed, and a new concept for Crimson was formulated by Fripp, including a front-line trio of drummers, the return after forty years of the amazing Mel Collins on flute and saxes, the always-reliable Levin, and the introduction of Jakko Jakszyk on vocals and guitar.

In 2014, the band came to Los Angeles and played the beautiful old Orpheum Theatre and, after thirty years, it was quite a sight to see Crimson again. The first half-hour, though, was a challenge trying to acclimate to the massive wall of sound created by drummers Pat Mastellotto, Bill Rieflin and Gavin Harrison. All of them are fantastic at their instrument, but it did take that time to adjust to hearing the din and, probably, they were still working out the dynamics of playing together.

In 2017, the band was back, though were now four drummers with the addition of the unknown Jeremy Stacy and he and Rieflin also played keyboards. The June show at the Greek was also very enjoyable and the band played really well.

BUT, the seven-piece (Rieflin sat out this tour) that walked onto the stage at the Greek on Tuesday sounded miles ahead of that excellent ensemble and it was the trio of drummers who really propelled the band forward in what can only be described as a powerful, thrilling and stunning performance by a thoroughly road-tested and stage-hardened juggernaut.

The truth is that everyone played great. Mel Collins was fantastic on his various saxes and flutes and even threw in bits of old tunes like "Tequila" to build the fun that isn't always associated with the band. Levin is always awesome, providing just the right amount of low end to hold everything together, including playing with three monster drummers. Jakszyk was in top vocal form and seemed much more comfortable with tunes associated with great vocalists like the late Greg Lake and John Wetton as well as Belew.

As for Fripp, it is abundantly clear that he is vastly more energized and playing with far more enjoyment with this group than at any time. As with earlier shows, his guitar may have been given a little less volume than it could be, but his playing demonstrates the enthusiasm of working with an ensemble at its peak level of performance.

The Radical Action to Unseat the Hold of Monkey Mind box set includes three CDs of live performances from 2015, with discs devoted to "Mainly Metal," "Easy Money Shots," and "Crimson Classics" and shows the band gelling to the degree that the type of telepathic interplay, between the three drummers and the ensemble generally, was becoming institutionalized, but not in a robotic rote way.

The added benefit are three discs (one Blu-Ray and two standard DVDs) of videos of live performances, so that the ensemble can be seen as well as heard generating the reworking of so much classic material, along with some newer pieces.

Who knows whether this 50th anniversary tour means in terms of the future of King Crimson, but the concert was remarkable and this longest-lasting incarnation seems primed to keep going and audiences are there to support it.

Friday, August 16, 2019

Anthony Braxton and Marilyn Crispell: Duets, Vancouver, 1989

Wednesday night was the fulfillment of a long-deferred dream—to hear Anthony Braxton live. I bought his Antilles release Six Compositions when it was released in 1991 and, in the years since, have purchased and avidly listened to dozens of recordings in his prodigious discography since.

The setting last evening was highly unusual. The Broad, the contemporary art museum opened four years ago by Los Angeles capitalist Eli Broad, has an exhibit on contemporary black art and a music component was introduced. This included Braxton performing a duet with harpist Jacqueline Kerrod in the lobby of the institution.

On one hand, this was an odd and jarring setting with many museum visitors walking past, some talking very loudly, and, behind Braxton and Kerrod, pedestrians and vehicles moving past on Grand Avenue. The usual setting of attendees sitting and having their attention (should they enjoy what they're hearing, that is) fixated on the performers was completely turned on its head.

Yet, there was something intriguing and compelling about the environment, though maybe the external elements and forces melted away simply because Braxton and Kerrod created a spellbinding performance over about an hour and ten minutes that drew the attentive listener in and kept them locked in due to the remarkable interplay and stellar playing.

I was also transported back to the early Nineties when I went frequently to the old Catalina Bar and Gill on Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood to hear some of my favorite musicians, including McCoy Tyner, Horace Tapscott, Elvin Jones, and many others. After figuring out that, if I got there early enough to be in front of the line, and got to be known, at least by sight, to Catalina Popescu and her husband Bob, it was usually easy to get a bistro table and two chairs at the front and literally be inches from some of the greatest musicians in the world. Having been to hundreds of rock concerts where the separation was notable, the intimacy of the jazz club was intoxicating.

At the Broad, I wasn't right up front, but got within several feet after slowly sliding my way forward as casual listeners wandered away. Literally, drawn in. Kerrod was tremendous, being very much in tune with what Braxton was doing, and playing traditional runs on the harp, but also engaging in scraping, plucking and tapping in very experimental but always supportive ways.

In turn, Braxton gave her plenty of space, played off her ideas, and then wandered thrillingly through the registers of his alto, soprano and sopranino saxophones. If silence was called for, he made full use of it, as well as the use of staccato notes, blistering runs (at 74, he appears to have lost none of his staggering technique), slurs and smears, and other elements.

In fact, despite his cold and academic reputation and there was some notation (or at least, figures and drawings) on music stands, I found much of what he did very soulful and emotive. Perhaps this was in response to the Kerrod's harp, because he did play more of the higher register saxes than the alto and it worked beautifully with her playing.

At the end, following sustained and enthusiastic applause from those of us who stood the entire time and were maybe half of who started off listening, Braxton spoke emotionally about his return to the city after so many years and expressed hope that change would come to the country, an obvious reference to the turmoil experienced in America (Braxton has long expressed the idea that music can directly affect life in the universe).

After he walked off the small stage, I went over to Braxton, shook his hand, and merely said, "I want to thank you for this. I've been waiting thirty years [OK, twenty-eight] to hear you. Thanks again" and wandered out with my wife (who was a trouper for putting up with this, even though she had to sit on the floor for the last fifteen or so minutes.)

Definitely a night to remember and, again, a long-held ambition realized.

The highlighted recording here from the Music & Arts label is another fabulous duet, one of many in Braxton's long and storied career. In this performance with the stunning pianist Marilyn Crispell, whose music has been covered here before, the telepathic interplay is just amazing to behold. Crispell remains a largely unknown figure in modern music, which is really a shame, because, as Braxton says in the notes"I believe her music will be considered required listening by future students of exploratory creative music."

He adds, "she can execute in every area (and even more importantly, she creative contributes,)" which allows Braxton to roam freely through marches, notated music, and totally improvised work with a sense of organic harmony that is phenomenal. For all of his talk of "my evolving music system of interconnected identity/states" or "material [which] forms the evolving architectural 'tri-state' of my vibrational model," there is a rare level of sympathetic hearing and playing between Braxton and Crispell which is found in his best duo works, as well as other larger ensembles, including the quartet with the pair and Gerry Hemingway and Mark Dresser, best known through the quartet work of the Eighties.

This is a longer post than usual, but the experience of hearing Braxton, who said he hadn't been to Los Angeles in twenty years, with Kerrod as an excellent collaborator, brought to mind this wonderful recording from just before I started listening to this modern musical master.

The setting last evening was highly unusual. The Broad, the contemporary art museum opened four years ago by Los Angeles capitalist Eli Broad, has an exhibit on contemporary black art and a music component was introduced. This included Braxton performing a duet with harpist Jacqueline Kerrod in the lobby of the institution.

On one hand, this was an odd and jarring setting with many museum visitors walking past, some talking very loudly, and, behind Braxton and Kerrod, pedestrians and vehicles moving past on Grand Avenue. The usual setting of attendees sitting and having their attention (should they enjoy what they're hearing, that is) fixated on the performers was completely turned on its head.

Yet, there was something intriguing and compelling about the environment, though maybe the external elements and forces melted away simply because Braxton and Kerrod created a spellbinding performance over about an hour and ten minutes that drew the attentive listener in and kept them locked in due to the remarkable interplay and stellar playing.

I was also transported back to the early Nineties when I went frequently to the old Catalina Bar and Gill on Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood to hear some of my favorite musicians, including McCoy Tyner, Horace Tapscott, Elvin Jones, and many others. After figuring out that, if I got there early enough to be in front of the line, and got to be known, at least by sight, to Catalina Popescu and her husband Bob, it was usually easy to get a bistro table and two chairs at the front and literally be inches from some of the greatest musicians in the world. Having been to hundreds of rock concerts where the separation was notable, the intimacy of the jazz club was intoxicating.

At the Broad, I wasn't right up front, but got within several feet after slowly sliding my way forward as casual listeners wandered away. Literally, drawn in. Kerrod was tremendous, being very much in tune with what Braxton was doing, and playing traditional runs on the harp, but also engaging in scraping, plucking and tapping in very experimental but always supportive ways.

In turn, Braxton gave her plenty of space, played off her ideas, and then wandered thrillingly through the registers of his alto, soprano and sopranino saxophones. If silence was called for, he made full use of it, as well as the use of staccato notes, blistering runs (at 74, he appears to have lost none of his staggering technique), slurs and smears, and other elements.

In fact, despite his cold and academic reputation and there was some notation (or at least, figures and drawings) on music stands, I found much of what he did very soulful and emotive. Perhaps this was in response to the Kerrod's harp, because he did play more of the higher register saxes than the alto and it worked beautifully with her playing.

At the end, following sustained and enthusiastic applause from those of us who stood the entire time and were maybe half of who started off listening, Braxton spoke emotionally about his return to the city after so many years and expressed hope that change would come to the country, an obvious reference to the turmoil experienced in America (Braxton has long expressed the idea that music can directly affect life in the universe).

After he walked off the small stage, I went over to Braxton, shook his hand, and merely said, "I want to thank you for this. I've been waiting thirty years [OK, twenty-eight] to hear you. Thanks again" and wandered out with my wife (who was a trouper for putting up with this, even though she had to sit on the floor for the last fifteen or so minutes.)

Definitely a night to remember and, again, a long-held ambition realized.

The highlighted recording here from the Music & Arts label is another fabulous duet, one of many in Braxton's long and storied career. In this performance with the stunning pianist Marilyn Crispell, whose music has been covered here before, the telepathic interplay is just amazing to behold. Crispell remains a largely unknown figure in modern music, which is really a shame, because, as Braxton says in the notes"I believe her music will be considered required listening by future students of exploratory creative music."

He adds, "she can execute in every area (and even more importantly, she creative contributes,)" which allows Braxton to roam freely through marches, notated music, and totally improvised work with a sense of organic harmony that is phenomenal. For all of his talk of "my evolving music system of interconnected identity/states" or "material [which] forms the evolving architectural 'tri-state' of my vibrational model," there is a rare level of sympathetic hearing and playing between Braxton and Crispell which is found in his best duo works, as well as other larger ensembles, including the quartet with the pair and Gerry Hemingway and Mark Dresser, best known through the quartet work of the Eighties.

This is a longer post than usual, but the experience of hearing Braxton, who said he hadn't been to Los Angeles in twenty years, with Kerrod as an excellent collaborator, brought to mind this wonderful recording from just before I started listening to this modern musical master.

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Camarão Plays Forró: Dance Music From Northeastern Brazil

This is fabulous music from northeastern Brazil with emphasis on virtuoso accordion playing by Reginaldo Alves Ferreira, known as Camarão (shrimp in Poruguese because of a sunburn he once sported in the studio), who gets billing and a few pieces by Arlindo Dos Oito Baixos, whose work with the eight-bass button accordion is featured on four pieces.

Released in 1998 on the great British label Nimbus, which has issued so many remarkable recordings of world music, this album's music employs several styles including forró, baião, xote, arrastapé and chachado, which are basically unknown to most foreign listeners who identify Brazilian music with the samba and bossa nova.

This is also more country music, though migrants seeking work and better opportunities have brought the music of the northeast to the large cities of the south. Accompanying the accordions on these pieces are light percussion on the triangle, cow bells and bass drum, while some guitar and vocals are interspersed, giving the tunes additional variety.

Camarão was quoted in the liner notes about the importance of not "modernizing too much" and keeping tradition in a way that was "essentially simple and direct," while he strives to "play music that smells of the land" in his native Pernambuco town of Caruarú.

In America, we think of dance music as often very beat heavy, whereas this music is light and airy, with the mastery of the accordion sensitively complemented by the other instruments and the vocals also treading softly but with much melodic emphasis. This is a gorgeous recording not often heard here and a welcome addition to the fine collection of world music offered by Nimbus.

Released in 1998 on the great British label Nimbus, which has issued so many remarkable recordings of world music, this album's music employs several styles including forró, baião, xote, arrastapé and chachado, which are basically unknown to most foreign listeners who identify Brazilian music with the samba and bossa nova.

This is also more country music, though migrants seeking work and better opportunities have brought the music of the northeast to the large cities of the south. Accompanying the accordions on these pieces are light percussion on the triangle, cow bells and bass drum, while some guitar and vocals are interspersed, giving the tunes additional variety.

Camarão was quoted in the liner notes about the importance of not "modernizing too much" and keeping tradition in a way that was "essentially simple and direct," while he strives to "play music that smells of the land" in his native Pernambuco town of Caruarú.

In America, we think of dance music as often very beat heavy, whereas this music is light and airy, with the mastery of the accordion sensitively complemented by the other instruments and the vocals also treading softly but with much melodic emphasis. This is a gorgeous recording not often heard here and a welcome addition to the fine collection of world music offered by Nimbus.

Monday, April 29, 2019

Mick Harris: Hednod Sessions

This two-disc set released in 2004 on Hidden Art Recordings were culled from sessions created by the former Napalm Death drummer who turned to dark, slow tempo electronics in all kinds of guises including Scorn, Lull, Quoit and in many collaborations, but who has largely been silent for a number of years.

Harris' forte consists forbidding washes and undercurrents of processed sound over steady, heavy beats, or, as often was the case with Lull, pulses. Variability is often subtle and slowly evolving and the simplicity can be deceiving when he introduces change in ways that are disarming. While Scorn was generally very heavy on the beats and Lull increasingly mitigated them with a glacial pace of change in pulse, the Hednod Sessions strike something of an (un)happy medium.

These thirty tracks were created in 1999 in Harris' minuscule home studio, a converted bathroom labeled "The Box." They were initially issued as a quartet of 12" singles on the hushhush label with additional tracks provided to subscribers of a series comprising the four sessions and five bonus pieces added later.

As befits the location where these works were created, there is often a claustrophobic, or, if preferred, intimate sense in hearing these pieces. Some of this is the muted percussion, but a great deal of the effect comes from the eerie employment of sound sources. There is something compellingly immersive about listening to these recordings, especially with headphones.

In instances like this, Harris can be at his most appealing and interesting when he creates that atmosphere and environment in music that essentially consumes the full attention of a dedicated listener. Again, the results tend to be best appreciated by focusing attention on the subtleties of the sound as it works through and around the steady application of rhythm.

When this set was purchased new some fifteen years ago, the shock was that it was acquired extremely cheaply—literally a few dollars on eBay—for reasons that remain a mystery. This is hardly a "you get what you pay for" statement, but it did seem like a stroke of great fortune in getting such a bargain for such utterly absorbing sound worlds.

Harris' forte consists forbidding washes and undercurrents of processed sound over steady, heavy beats, or, as often was the case with Lull, pulses. Variability is often subtle and slowly evolving and the simplicity can be deceiving when he introduces change in ways that are disarming. While Scorn was generally very heavy on the beats and Lull increasingly mitigated them with a glacial pace of change in pulse, the Hednod Sessions strike something of an (un)happy medium.

These thirty tracks were created in 1999 in Harris' minuscule home studio, a converted bathroom labeled "The Box." They were initially issued as a quartet of 12" singles on the hushhush label with additional tracks provided to subscribers of a series comprising the four sessions and five bonus pieces added later.

As befits the location where these works were created, there is often a claustrophobic, or, if preferred, intimate sense in hearing these pieces. Some of this is the muted percussion, but a great deal of the effect comes from the eerie employment of sound sources. There is something compellingly immersive about listening to these recordings, especially with headphones.

In instances like this, Harris can be at his most appealing and interesting when he creates that atmosphere and environment in music that essentially consumes the full attention of a dedicated listener. Again, the results tend to be best appreciated by focusing attention on the subtleties of the sound as it works through and around the steady application of rhythm.

When this set was purchased new some fifteen years ago, the shock was that it was acquired extremely cheaply—literally a few dollars on eBay—for reasons that remain a mystery. This is hardly a "you get what you pay for" statement, but it did seem like a stroke of great fortune in getting such a bargain for such utterly absorbing sound worlds.

John Zorn/George Lewis/Bill Frisell: News for Lulu

For all his reputation as a musical enfant terrible in the late 1980s, master saxophonist and composer John Zorn could create some pretty accessible and impressive recordings. His 1988 album News for Lulu with compatriots George Lewis and Bill Frisell and released on the Swiss Hat Hut label is perhaps the best example of this.

Just as importantly, this amazing album is a heartfelt and deeply respectful tribute to some of the most talented, but not as well known jazz composers of so-called post-bop period of the 1950s. Zorn, a master saxophonist with an impeccable pedigree in jazz (best epitomized by his staggering Masada quartet) built News for Lulu on compositions from Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Sonny Clark and Freddie Redd.

These are not the familiar names of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins and other notables, but here Zorn gives them and their work their full due. As Peter Watrous points out in his liner notes essay, the musicians employ "hard bop as a base from which to build their own ideas on improvisation, arrangements, melodies."

Additionally, by eschewing a rhythm section of bass, drums and piano, Zorn and his partners "expose the way the tunes work, making them even more intense, and taking the project out of the constrains of the jazz tradition." Art Lange, in his remarks, observed that the trio could play these tunes largely as conceived "or break free into contrapuntal abandon, energized every step of the way by bebop's enthusiastic buoyancy and an added jolt of 80s adventurism."

Zorn added his own reflections, emphasizing the telepathic interplay he shared with trombonist Lewis and Frisell, whose wider exposure as a guitarist was yet to come. He highlighted the former's "beautiful sense of harmony and counterpoint," while the latter "kills you with one of his tasty country funk lines" and his "tonal blend."

As challenging as Zorn's music could be in these early years, News for Lulu is a paramount example of how he could experiment and yet provide a clear listenable experience.

Just as importantly, this amazing album is a heartfelt and deeply respectful tribute to some of the most talented, but not as well known jazz composers of so-called post-bop period of the 1950s. Zorn, a master saxophonist with an impeccable pedigree in jazz (best epitomized by his staggering Masada quartet) built News for Lulu on compositions from Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Sonny Clark and Freddie Redd.

These are not the familiar names of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins and other notables, but here Zorn gives them and their work their full due. As Peter Watrous points out in his liner notes essay, the musicians employ "hard bop as a base from which to build their own ideas on improvisation, arrangements, melodies."

Additionally, by eschewing a rhythm section of bass, drums and piano, Zorn and his partners "expose the way the tunes work, making them even more intense, and taking the project out of the constrains of the jazz tradition." Art Lange, in his remarks, observed that the trio could play these tunes largely as conceived "or break free into contrapuntal abandon, energized every step of the way by bebop's enthusiastic buoyancy and an added jolt of 80s adventurism."

Zorn added his own reflections, emphasizing the telepathic interplay he shared with trombonist Lewis and Frisell, whose wider exposure as a guitarist was yet to come. He highlighted the former's "beautiful sense of harmony and counterpoint," while the latter "kills you with one of his tasty country funk lines" and his "tonal blend."

As challenging as Zorn's music could be in these early years, News for Lulu is a paramount example of how he could experiment and yet provide a clear listenable experience.

Saturday, April 27, 2019

Franz Schubert: Piano Trios D.929 and D.897

The tragically short-lived composer Franz Schubert left behind a remarkable body of work in so compressed a span, including eight symphonies and the amazing unfinished ninth, lieder or songs of significant number and import, and a great many works for small ensembles.

This Naxos release from the late 1980s is a masterful recording by the Stuttgart Piano Trio, comprised of violinist Rainer Kusmaul, cellist Claus Kannglesser, and pianist Monika Leonhard, of two of the master's piano trios, the E-flat and the Nocturne.

The former is a stunning evocation of the form, spanning over 45 minutes through four movements. It displays beautiful melodicism, exquisite harmonies, powerful dynamics and superb playing. Composed in late 1827 for a friend's engagement and performed early the next year and then publicly in March, the trio is one of the few works the composer heard played during his brief life.

One observer notes that second movement of this piece was used in Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon and that the auteur noted that the trio "has just the right restrained balance between the tragic and the romantic. This could be said probably of much of Schubert's music as he bridged the eras of, say, Beethoven and Liszt.

The Nocturne was evidently a discarded draft of the andante second movement that Kubrick used and, even as an outtake of sorts, it is still a gorgeous piece of music. There is much dramatic interplay, quiet passages of deep emotion, virtuosic flutterings of notes on the piano that are noteworthy, and an overall synchronicity of the three instruments that make this single movement a fascinating complement to the massive and memorable E Flat Major trio.

This Naxos release from the late 1980s is a masterful recording by the Stuttgart Piano Trio, comprised of violinist Rainer Kusmaul, cellist Claus Kannglesser, and pianist Monika Leonhard, of two of the master's piano trios, the E-flat and the Nocturne.

The former is a stunning evocation of the form, spanning over 45 minutes through four movements. It displays beautiful melodicism, exquisite harmonies, powerful dynamics and superb playing. Composed in late 1827 for a friend's engagement and performed early the next year and then publicly in March, the trio is one of the few works the composer heard played during his brief life.

One observer notes that second movement of this piece was used in Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon and that the auteur noted that the trio "has just the right restrained balance between the tragic and the romantic. This could be said probably of much of Schubert's music as he bridged the eras of, say, Beethoven and Liszt.

The Nocturne was evidently a discarded draft of the andante second movement that Kubrick used and, even as an outtake of sorts, it is still a gorgeous piece of music. There is much dramatic interplay, quiet passages of deep emotion, virtuosic flutterings of notes on the piano that are noteworthy, and an overall synchronicity of the three instruments that make this single movement a fascinating complement to the massive and memorable E Flat Major trio.

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

Ustad Mohammad Omar: Virtuoso From Afghanistan

This 2002 release from the Smithsonian Folkways label was very timely in a political and cultural sense. The Taliban regime's retreat from Afghanistan in the aftermath of 9-11 and the American-led military mission there allowed for the return of music, which was made illegal by the Taliban.

Reference was made in the liner notes to a conference in Holland at which ethnomusicologists spoke about the effects of this edict on the musicians of that oft-suffering nation. There are also statements about in Islamic societies, music is a question of controversy, with religious conservatives condemning it as promoting undesirable behavior, while it was also pointed out that some of the most remarkable music from the Muslim world has been very spiritual.

Mohammad Omar (Ustad is a title referring to musical mastery) was the director of the National Orchestra of Afghanistan for many years and a virtuoso on the rabab, considered to be an ancestor of the Indian sarod (Ali Akbar Khan, for example, has been highlighted on this blog).

In November 1974, Omar performed live at the University of Washington and was accompanied by a young and not-well-known tabla player, Zakir Hussain. The two first met the morning of the concert and though they did not share a spoken language, their fluency in music easily compensated. They simply rehearsed and then put on a spectacular show. Omar died in 1980, so this was his sole recorded performance in America.

Fortunately, though it took nearly three decades, this stunning concert was remastered and issued by the storied label and it provides a rare opportunity to listen to classical Afghan music with accompaniment by Hussein, who is now widely recognized as a master of the tabla. The liner notes, as is typical for a Smithsonian Folkways release, provides helpful information on Afghan music, Omar and his instrument, the concert program, and Hussain.

Reference was made in the liner notes to a conference in Holland at which ethnomusicologists spoke about the effects of this edict on the musicians of that oft-suffering nation. There are also statements about in Islamic societies, music is a question of controversy, with religious conservatives condemning it as promoting undesirable behavior, while it was also pointed out that some of the most remarkable music from the Muslim world has been very spiritual.

Mohammad Omar (Ustad is a title referring to musical mastery) was the director of the National Orchestra of Afghanistan for many years and a virtuoso on the rabab, considered to be an ancestor of the Indian sarod (Ali Akbar Khan, for example, has been highlighted on this blog).

In November 1974, Omar performed live at the University of Washington and was accompanied by a young and not-well-known tabla player, Zakir Hussain. The two first met the morning of the concert and though they did not share a spoken language, their fluency in music easily compensated. They simply rehearsed and then put on a spectacular show. Omar died in 1980, so this was his sole recorded performance in America.

Fortunately, though it took nearly three decades, this stunning concert was remastered and issued by the storied label and it provides a rare opportunity to listen to classical Afghan music with accompaniment by Hussein, who is now widely recognized as a master of the tabla. The liner notes, as is typical for a Smithsonian Folkways release, provides helpful information on Afghan music, Omar and his instrument, the concert program, and Hussain.

Macro Dub Infection, Volume One

This is a fascinating two-disc set issued in 1995 on Virgin Records with American distribution by Caroline Records that is an absorbing fusion of dub and electronica. Among the familiar names to this listener are Automaton (a Bill Laswell project), Coil, Laika, The Golden Palominos (Anton Fier and company), Tricky, Scorn (Mick Harris), and Mad Professor.

Some of this music is far more directly tied to dub, while others are more of an electronica vein, though the use of studio experimentation with the manipulation of sound, so maybe trying to parse out what is "dub" is a pointless exercise. Moreover, that doesn't make any of these pieces intrinsically better than others or a better work because it has a dub connotation.

Still, the quality of these 23 tracks is uniformly high and intriguing, Also interesting are the liner notes bearing the heading of "Scientist Meets the Ghost Captain," and which are comprised of dated comments, though not in chronological order, from 1955-1995.

Put together by the album's compiler, K. Martin, these notes include quotes from famed reggae and dub figures like Lee "Scratch" Perry and Augustus Pablo, avant-garde literary figures such as William S. Burroughs and Marshall McLuhan, and musical experimenters including George Russell and John Zorn. Martin's text about dub and other experimental forms of musical experimentation and broad cultural statements are striking, if disjointed. That, though, might be the point, a la Burroughs' "cut-up" approach.

In any case, Macro Dub Infection, Volume One is a mind-bending and enjoyable excursion into the many intersections of electronic music and dub and well worth the effort to locate. A second volume, not as strong as the first, was issued in 1996, but is still very enjoyable.

Some of this music is far more directly tied to dub, while others are more of an electronica vein, though the use of studio experimentation with the manipulation of sound, so maybe trying to parse out what is "dub" is a pointless exercise. Moreover, that doesn't make any of these pieces intrinsically better than others or a better work because it has a dub connotation.

Still, the quality of these 23 tracks is uniformly high and intriguing, Also interesting are the liner notes bearing the heading of "Scientist Meets the Ghost Captain," and which are comprised of dated comments, though not in chronological order, from 1955-1995.

Put together by the album's compiler, K. Martin, these notes include quotes from famed reggae and dub figures like Lee "Scratch" Perry and Augustus Pablo, avant-garde literary figures such as William S. Burroughs and Marshall McLuhan, and musical experimenters including George Russell and John Zorn. Martin's text about dub and other experimental forms of musical experimentation and broad cultural statements are striking, if disjointed. That, though, might be the point, a la Burroughs' "cut-up" approach.

In any case, Macro Dub Infection, Volume One is a mind-bending and enjoyable excursion into the many intersections of electronic music and dub and well worth the effort to locate. A second volume, not as strong as the first, was issued in 1996, but is still very enjoyable.

Sunday, March 24, 2019

Peter Brötzmann/Die Like a Dog Quartet: Little Birds Have Fast Hearts, Nos 1-2

Though it appears neither was aware of the other's work at the time, the parallels between the "free jazz" saxophonists American Albert Ayler and German Peter Brötzmann, are striking. Both gloried in the sheer joy of expression in ecstatic sound when they emerged in the mid-1960s as "free jazz" exploded. Not that their music sounded exactly the same and Ayler definitely had a heavily spiritual motivation that Brötzmann did not seem to have, but the unbridled energy that blared from their instruments definitely had some sort of kinship in the exploration of pure sound.

Ayler blazed trails and infuriated purists during his brief, but bracing peak blasts of powerful live and studio recordings from 1964 to 1967 before ill-advised attempts to reach a more popular audience through albums on Impulse Records failed badly. There was a late attempt to regain his footing with some recorded live performances in Europe in summer 1970. Then, in November, the great saxophonist disappeared after an argument with his girlfriend and his body was found floating in the East River near a pier in Brooklyn. His drowning death remains a mystery and adds to the legend of the man called "Little Bird," in homage to his skills and comparisons to Charlie Parker.

Brötzmann, when he learned of Ayler's music became a devoted fan, and nearly thirty years after Ayler's death, formed a quartet called Die Like a Dog, an apparent reference to Ayler's passing. A series of performances in November 1997 at a festival in Berlin yielded two volumes of stunning improvised music released first by FMP (Free Music Productions) and then by Jazzwerkstatt in a Die Like a Dog box set as Little Birds Have Fast Hearts, an encomium to Ayler.

From his ragged, wild and utterly intense early recordings like Machine Gun, For Adolphe Sax, and Nipples, among others, Brötzmann's career is still defined by his refusal to record much in the studio and his preference for the total spontaneity and freedom of live performance, though some of that sheer power has morphed into some reflective and introspective music.

Little Birds Have Fast Hearts has plenty of wild, careening and bracing moments over its 126 minutes in six parts, but there are also lots of moments where the music slows and thoughtful passages break up the intensity. Fortunately, Brötzmann assembled an ensemble that could provide him the sensitive and near-telepathic accompaniment that make these recording so spectacular.

Toshinori Kondo is a perfect complement and foil, being known for his electronic treatments of his trimpet as well as his medium and slower tempo ruminations on this most emotive of wind instruments. Kondo, a frequent collaborator like Brötzmann of Bill Laswell, makes the most of his style here, tempering the intensity of Brötamann's tenor, clairnet, and taogato with a consistent flow of bubbling and moderated energy.

The rhythm section is vital, because bassist William Parker and drummer Hamid Drake, know how to hold down the bottom and yet work fluidly and with lightning quick reactions to the playing of the lead horns. Their superb accompaniment never seeks to take the forefront, but keeps everything together perfectly, so that Brötzmann and Kondo can give flight to their fancies. This makes Little Birds Have Fast Hearts a classic of free improvisation and worth repeated listenings, guaranteed to reveal more depth, nuance and excitement each time.

Ayler blazed trails and infuriated purists during his brief, but bracing peak blasts of powerful live and studio recordings from 1964 to 1967 before ill-advised attempts to reach a more popular audience through albums on Impulse Records failed badly. There was a late attempt to regain his footing with some recorded live performances in Europe in summer 1970. Then, in November, the great saxophonist disappeared after an argument with his girlfriend and his body was found floating in the East River near a pier in Brooklyn. His drowning death remains a mystery and adds to the legend of the man called "Little Bird," in homage to his skills and comparisons to Charlie Parker.

Brötzmann, when he learned of Ayler's music became a devoted fan, and nearly thirty years after Ayler's death, formed a quartet called Die Like a Dog, an apparent reference to Ayler's passing. A series of performances in November 1997 at a festival in Berlin yielded two volumes of stunning improvised music released first by FMP (Free Music Productions) and then by Jazzwerkstatt in a Die Like a Dog box set as Little Birds Have Fast Hearts, an encomium to Ayler.

From his ragged, wild and utterly intense early recordings like Machine Gun, For Adolphe Sax, and Nipples, among others, Brötzmann's career is still defined by his refusal to record much in the studio and his preference for the total spontaneity and freedom of live performance, though some of that sheer power has morphed into some reflective and introspective music.

Little Birds Have Fast Hearts has plenty of wild, careening and bracing moments over its 126 minutes in six parts, but there are also lots of moments where the music slows and thoughtful passages break up the intensity. Fortunately, Brötzmann assembled an ensemble that could provide him the sensitive and near-telepathic accompaniment that make these recording so spectacular.

Toshinori Kondo is a perfect complement and foil, being known for his electronic treatments of his trimpet as well as his medium and slower tempo ruminations on this most emotive of wind instruments. Kondo, a frequent collaborator like Brötzmann of Bill Laswell, makes the most of his style here, tempering the intensity of Brötamann's tenor, clairnet, and taogato with a consistent flow of bubbling and moderated energy.

The rhythm section is vital, because bassist William Parker and drummer Hamid Drake, know how to hold down the bottom and yet work fluidly and with lightning quick reactions to the playing of the lead horns. Their superb accompaniment never seeks to take the forefront, but keeps everything together perfectly, so that Brötzmann and Kondo can give flight to their fancies. This makes Little Birds Have Fast Hearts a classic of free improvisation and worth repeated listenings, guaranteed to reveal more depth, nuance and excitement each time.

Saturday, March 23, 2019

Iannis Xenakis: Persepolis + Remixes Edition 1

The context for Persepolis is, by any standard, strange, but fascinating. The Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, decided, in 1971, to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of Persia by Cyrus the Great by holding an event that also was intended to justify the Shah's place in Persian history, though eight years later he was deposed by a conservative religious revolution.

As part of the festivities, the Shah commissioned composer Iannis Xenakis to create a piece of music and the result is the astounding Persepolis, named for the city built by Cyrus and the ruins of which are in the deserts of the south part of the country. As a symbol of the ancient power and might of the Persian Empire, Persepolis became the basis for an extraordinary piece of music as extreme sound that seems totally alien to that society and for that matter most modern ears!

This listener finds the nearly hour-long work on eight-channel tape, with this 2002 version on Asphodel Records based on the original tapes with consultation of Xenakis, to be compelling as a gradual build-up of sound that may not conjure up anything specific about ancient Persia or Persepolis. There is a haunting and desolate feel that does not remotely sound celebratory.

Xenakis, however, latched on to a crucial concept in Zoroastrianism, the religion of the ancient Persians, involving the binary conflict of darkness and light. The piece, blared through nearly 60 loudspeakers, also emphasized light, through torches and bonfires (ancient light) and lasers and bright electrical light (modern forms). It is hard to imagine that attendees were anything but stunned and confused by the spectacle.

The composer said that Persepolis was reflective of "history's noises" and the mechanical sounds, high-pitched percussion sounding like dragged objects, echoed hisses and howls seem to indicate a primeval passage through the turmoil of history. It is disconcerting, but also hypnotic when concentrated attention is placed, especially in the last ten minutes, which is incredibly intense.

A second disc of remixes by electronic artists from Japan, Spain, Poland, Germany and the United States are varied and often bear little over resemblance to Xenakis' piece, but, as is often the case, take basic inspiration as a means to express general affinity and kinship about the nature of extreme sound.

To this listener, hearing Persepolis is somewhat akin to hearing Lou Reed's confounding, but remarkable, Metal Machine Music, including its stunning notated reproduction by Zeitkratzer. What could seem like a joke or complete self-indulgence takes on an aura of inspired explorations of the outer limits of music, espcially considering the strange relationship of Xenakis, a modernist, avant- garde musical revolutionary and the autocratic Shah not long removed from an ignominious end.

As part of the festivities, the Shah commissioned composer Iannis Xenakis to create a piece of music and the result is the astounding Persepolis, named for the city built by Cyrus and the ruins of which are in the deserts of the south part of the country. As a symbol of the ancient power and might of the Persian Empire, Persepolis became the basis for an extraordinary piece of music as extreme sound that seems totally alien to that society and for that matter most modern ears!

This listener finds the nearly hour-long work on eight-channel tape, with this 2002 version on Asphodel Records based on the original tapes with consultation of Xenakis, to be compelling as a gradual build-up of sound that may not conjure up anything specific about ancient Persia or Persepolis. There is a haunting and desolate feel that does not remotely sound celebratory.

Xenakis, however, latched on to a crucial concept in Zoroastrianism, the religion of the ancient Persians, involving the binary conflict of darkness and light. The piece, blared through nearly 60 loudspeakers, also emphasized light, through torches and bonfires (ancient light) and lasers and bright electrical light (modern forms). It is hard to imagine that attendees were anything but stunned and confused by the spectacle.

The composer said that Persepolis was reflective of "history's noises" and the mechanical sounds, high-pitched percussion sounding like dragged objects, echoed hisses and howls seem to indicate a primeval passage through the turmoil of history. It is disconcerting, but also hypnotic when concentrated attention is placed, especially in the last ten minutes, which is incredibly intense.

A second disc of remixes by electronic artists from Japan, Spain, Poland, Germany and the United States are varied and often bear little over resemblance to Xenakis' piece, but, as is often the case, take basic inspiration as a means to express general affinity and kinship about the nature of extreme sound.

To this listener, hearing Persepolis is somewhat akin to hearing Lou Reed's confounding, but remarkable, Metal Machine Music, including its stunning notated reproduction by Zeitkratzer. What could seem like a joke or complete self-indulgence takes on an aura of inspired explorations of the outer limits of music, espcially considering the strange relationship of Xenakis, a modernist, avant- garde musical revolutionary and the autocratic Shah not long removed from an ignominious end.

Safarini In Transit: Music of African Immigrants

Here is another stellar Smithsonian Folkways release, issued in 2000 and presenting the vibrant music of African immigrants who'd settled in Seattle and Portland and maintained their musical traditions while living in a new society worlds away from their homelands.

The music here is uniformly entertaining and a lot of fun to listen to, with some performers having recorded frequently, like Obo Addy, and others appearing on an album for the first time, but they are all excellent in presenting their diverse contributions. Addy is the best-known, having released a number of albums on his own and appearing on the Kronos Quartet's Pieces of Africa.

Lora Chiorah-Dye, Kofi Anang, Frank Ulwenya, Wawali Bonane and Yoka Nzenze are among the featured artists and they represent the musical traditions of such disparate parts of the African continent as Zimbabwe, Ghana, Kenya and the Congo. There is a great blending here of traditional instruments, rhythms and vocalizing with Western instrumentation, like drum kits, guitar, bass and horns, showing the fusion of music and instruments at its best.

Also very useful (and a main reason why CDs are worth having) are the liner notes, featuring short essays by Diana N'Diaye on African immigrants in America and Jon Kertzer on African musicians in the Pacific Northwest. These are interesting and informative, along with the detailed discussion of the pieces and the performers that follows.

It is also significant that this recording was put together in collaboration with strong community organizations in Seattle, including Rakumi Arts International, which promotes education about Africa broadly including music, and Jack Straw Productions, an audio arts center founded in the early 1960s and its Artist Support Program was key to the development of Safarini.

The music here is uniformly entertaining and a lot of fun to listen to, with some performers having recorded frequently, like Obo Addy, and others appearing on an album for the first time, but they are all excellent in presenting their diverse contributions. Addy is the best-known, having released a number of albums on his own and appearing on the Kronos Quartet's Pieces of Africa.

Lora Chiorah-Dye, Kofi Anang, Frank Ulwenya, Wawali Bonane and Yoka Nzenze are among the featured artists and they represent the musical traditions of such disparate parts of the African continent as Zimbabwe, Ghana, Kenya and the Congo. There is a great blending here of traditional instruments, rhythms and vocalizing with Western instrumentation, like drum kits, guitar, bass and horns, showing the fusion of music and instruments at its best.

Also very useful (and a main reason why CDs are worth having) are the liner notes, featuring short essays by Diana N'Diaye on African immigrants in America and Jon Kertzer on African musicians in the Pacific Northwest. These are interesting and informative, along with the detailed discussion of the pieces and the performers that follows.

It is also significant that this recording was put together in collaboration with strong community organizations in Seattle, including Rakumi Arts International, which promotes education about Africa broadly including music, and Jack Straw Productions, an audio arts center founded in the early 1960s and its Artist Support Program was key to the development of Safarini.

Saturday, March 9, 2019

Wire: Change Becomes Us

Having recently read Wilson Neate's very detailed biography of Wire, one of the main themes of the book was the struggle between creating experimental art music and also having enough pop sensibilities to sell some records and keep the project viable. The book makes clear that the push-and-pull was largely between Bruce Gilbert, who was dedicated completely to the former, and Colin Newman, who liked to experiment (especially on his solo albums) but also pushed to have enough accessibility to make sure the band could survive in the marketplace.

The 2004 album Send, a bracing, remarkable record that seems to strike a balance and which was, according to the book, Newman and Gilbert working closely together to reconcile their varying tendencies, proved to be the end of the band's original lineup. Gilbert left soon after and has not been particularly active on recordings, though he has worked on other projects more to his liking.

As for Wire, they kept on, working with other guitarists before having Matthew Simms, a much younger musician, join the band as an official member. Neate's book points out that the group has become much more of what Newman had always intended and, whatever the success of that might be, Wire very much remains an active and intriguing band. Not as experimental as it once was, but for gents of a certain age and given how few bands of the late Seventies are still making original and viable music, the group consistently delivers great music.

In 2013, Wire put out Change Becomes Us, in which the quartet revisited and retooled a group of songs from more than thirty years prior, many of which were to be on an album following their first trio of classics: Pink Flag, Chairs Missing, and 154. The band imploded before that record could be made and the strange, though fascinating, Document and Eyewitness, featured live "performance art" renditions of many of these tunes, while others appeared in various iterations elsewhere.

Change Becomes Us is an intriguing project, taking songs that in most cases successfully blend accessbility with experimentation and presenting them in the "modern" Wire format, honed since Gilbert's departure. Robert Grey's steady precision continues to be essential, Graham Lewis' bass also anchors the tunes with fluidity and solidity and his lyrics are always interesting and arresting and Simms helps flesh out the sound in understated, but important, ways.

For those of us who only got the barest of glimpses into the possibility of what Document and Eyewitness and other sources hinted at, Change Becomes Us is a realization that shows that the ideas were largely sound and that the recent development of the band provides a maturity and craftsmanship that shows that Wire has so much to offer more than four decades after it first made a splash in the punk era.

The 2004 album Send, a bracing, remarkable record that seems to strike a balance and which was, according to the book, Newman and Gilbert working closely together to reconcile their varying tendencies, proved to be the end of the band's original lineup. Gilbert left soon after and has not been particularly active on recordings, though he has worked on other projects more to his liking.

|

| A previous owner of the disc put a sticker that could not be removed on the front cover, which is why only this much is shown! |

In 2013, Wire put out Change Becomes Us, in which the quartet revisited and retooled a group of songs from more than thirty years prior, many of which were to be on an album following their first trio of classics: Pink Flag, Chairs Missing, and 154. The band imploded before that record could be made and the strange, though fascinating, Document and Eyewitness, featured live "performance art" renditions of many of these tunes, while others appeared in various iterations elsewhere.

|

| So, as a consolation prize . . . |

For those of us who only got the barest of glimpses into the possibility of what Document and Eyewitness and other sources hinted at, Change Becomes Us is a realization that shows that the ideas were largely sound and that the recent development of the band provides a maturity and craftsmanship that shows that Wire has so much to offer more than four decades after it first made a splash in the punk era.

Sunday, March 3, 2019

Henry Threadgill Zooid: In for a Penny, In for a Pound

It was great to see a few years back the great composer and multi-instrumentalist Henry Threadgill receive the Pulitzer Prize in music for the double-disc In for a Penny, In for a Pound, released on Liberty Ellman's Pi Records, an honor very rarely bestowed on a jazz musician.

Ever since I walked into a record store (remember those?) just over twenty-five years ago and heard the amazing Too Much Sugar for a Dime and bought the store's playing copy because they didn't have any in stock, I've been a great admirer of this remarkable creative force.

Threadgill's concept for Zooid can be discerned in this dictionary definition of that term: any organic body or cell capable of spontaneous movement and of an existence more or less apart from or independent of the parent organism. So this looks to mean that spontaneous movement translates into improvisation and elements of an ensemble, soloists, rhythm section, etc. can operate "more or less apart" while staying within the group during a performance.

As he puts it in his notes, the album was conceived as "a stream of phases" for one long "epic" piece where the group "could revisit and find a new perspective and arrangement with each performance." Moreover, the each of the four pieces in quintets "focuses on a different instrument," though a listener would take in all of the pieces "to get the complete picture of any one instrument in the mix."

What's remarkable is how the ensemble works organically, while allowing for free expression within the long work and its component parts. The mix of winds through the work of Threadgill's alto sax and flutes and José Davila's tuba (in lieu of bass) and trombone are complemented by the strings in Christopher Hoffman's violoncello and Ellman's guitar. Keeping everything moving along is Elliot Humberto Kavee's drums and percussion.

It can't be said that In for a Penny, In for a Pound, being a Pulitzer Prize-winning album, is better than any other Threadgill work, but it is a fantastic excursion into how music can be structured and played with both exquisite care for the arrangement of instruments, component groups and parts, and the development of sound structures that are both challenging and, in their own way, accessible with open ears and minds.

Ever since I walked into a record store (remember those?) just over twenty-five years ago and heard the amazing Too Much Sugar for a Dime and bought the store's playing copy because they didn't have any in stock, I've been a great admirer of this remarkable creative force.

Threadgill's concept for Zooid can be discerned in this dictionary definition of that term: any organic body or cell capable of spontaneous movement and of an existence more or less apart from or independent of the parent organism. So this looks to mean that spontaneous movement translates into improvisation and elements of an ensemble, soloists, rhythm section, etc. can operate "more or less apart" while staying within the group during a performance.

As he puts it in his notes, the album was conceived as "a stream of phases" for one long "epic" piece where the group "could revisit and find a new perspective and arrangement with each performance." Moreover, the each of the four pieces in quintets "focuses on a different instrument," though a listener would take in all of the pieces "to get the complete picture of any one instrument in the mix."

What's remarkable is how the ensemble works organically, while allowing for free expression within the long work and its component parts. The mix of winds through the work of Threadgill's alto sax and flutes and José Davila's tuba (in lieu of bass) and trombone are complemented by the strings in Christopher Hoffman's violoncello and Ellman's guitar. Keeping everything moving along is Elliot Humberto Kavee's drums and percussion.

It can't be said that In for a Penny, In for a Pound, being a Pulitzer Prize-winning album, is better than any other Threadgill work, but it is a fantastic excursion into how music can be structured and played with both exquisite care for the arrangement of instruments, component groups and parts, and the development of sound structures that are both challenging and, in their own way, accessible with open ears and minds.

Saturday, March 2, 2019

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 5

What a remarkable story with Anton Bruckner, who may be one of the best classical composers you've never heard of. Bruckner (1824-1896) wrote eight symphonies and an unfinished one that are some of the most powerful, creative of the genre, massive works that, like those of Mahler and the operatic works of Bruckner's idol, Wagner, were the epitome of the monumental orchestral piece.

Bruckner came from northern Austria and, when he went to Vienna, the epicenter of so-called "serious music," he was ridiculed for his country appearance and manners. Moreover, the gentle and sensitive composer was convinced by friends that he needed to be more like Wagner and urged him to revise his works to the detriment of the originals.

This was especially true for the first four of his symphonies, though Georg Tintner, the conductor who recorded all the symphonies with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra for Naxos, observed that, with the fourth, the revisions helped, whereas, with the first, these degraded the original, which was much superior.

In his informative liner notes, Tintner observes that "the Fifth Symphony, the most intellectual of all Bruckner's works, is furthest removed from the seductive world of Wagner's harmony and orchestration." The conductor also wonders why this and the Sixth Symphony were not subjected to endless revisions as was true for the others. Yet, when it finally premiered just before Bruckner's death and nearly twenty years after it was composed, it was in a "discredited, reorchestrated and cut version."

Tintner's mission with his recording of all the Bruckner symphonies was to present them, as much as possible, as the composer intended. This untutored ear takes in the very soft openings to some of the movements, such as the first, and then either sudden dramatic passages or build-ups to great intensity and passion, with powerful dynamics driving the music to heights that are among the finest symphonic statements encountered (albeit with limited knowledge). Tintner does suggest that the phenomenal finale "is certainly one of the greatest" in the "symphonic literature."

These massive, intense symphonic works can go on for lengthy periods—this one stretching over 75 minutes—so they take a level of concentration and endurance from a listener and this one needs to be in the right mood to take these (including works like those of Mahler and Wagner) on, but they can be highly rewarding experiences. Bruckner's Fifth, with some of the best known of his majestic melodies, delivers when that mood is there.

Bruckner came from northern Austria and, when he went to Vienna, the epicenter of so-called "serious music," he was ridiculed for his country appearance and manners. Moreover, the gentle and sensitive composer was convinced by friends that he needed to be more like Wagner and urged him to revise his works to the detriment of the originals.

This was especially true for the first four of his symphonies, though Georg Tintner, the conductor who recorded all the symphonies with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra for Naxos, observed that, with the fourth, the revisions helped, whereas, with the first, these degraded the original, which was much superior.

In his informative liner notes, Tintner observes that "the Fifth Symphony, the most intellectual of all Bruckner's works, is furthest removed from the seductive world of Wagner's harmony and orchestration." The conductor also wonders why this and the Sixth Symphony were not subjected to endless revisions as was true for the others. Yet, when it finally premiered just before Bruckner's death and nearly twenty years after it was composed, it was in a "discredited, reorchestrated and cut version."

Tintner's mission with his recording of all the Bruckner symphonies was to present them, as much as possible, as the composer intended. This untutored ear takes in the very soft openings to some of the movements, such as the first, and then either sudden dramatic passages or build-ups to great intensity and passion, with powerful dynamics driving the music to heights that are among the finest symphonic statements encountered (albeit with limited knowledge). Tintner does suggest that the phenomenal finale "is certainly one of the greatest" in the "symphonic literature."

These massive, intense symphonic works can go on for lengthy periods—this one stretching over 75 minutes—so they take a level of concentration and endurance from a listener and this one needs to be in the right mood to take these (including works like those of Mahler and Wagner) on, but they can be highly rewarding experiences. Bruckner's Fifth, with some of the best known of his majestic melodies, delivers when that mood is there.

Thursday, February 28, 2019

Hoggar: Music of the Tuareg

This fascinating recording is about as far removed from the recent spectacle of the Grammy Awards as you can possibly get and is a reminder to me of why becoming familiar with so-called "world music," especially indigenous music, nearly thirty years ago was such a life-changing transformation in my music listening experience.

The term "Tuareg" is used in broad brush for peoples from five distinct confederations in the region encompassed by the African nations of Mali, Libya, Burkina Faso, Niger and Algeria with a focus on this recording on the Hoggar who live in the mountains of that name in Algeria.

This 1994 release is from the French label Chant du Monde and this is particularly striking in that Algeria was a French colony and only gained its independence in 1962 after a particularly brutal war of liberation. During this time, the Hoggar were grievously affected by the strife and, as the informative liners, note "the camel-drivers' songs, the flute and the fiddle are disappearing," a phenomenon that is sadly too common throughout the world.

Among the really impressive elements of this are the hypnotic hand-claps that accompany polyphonal singing and chanting in large group ensembles—the vocals can be haunting and otherwordly. The solo work of flutes and fiddles is also very interesting to hear, along with the teherdent, a lute-like instrument with great resonance that gives what seems like a blues feel to the performances.

Recordings like this really gives a different perspective on what music means as an everyday practice for people who are not professionals in the Western sense and it seems to this listener to get to the very marrow of what music is. Sometimes, a return to the essence is a way to recalibrate, whether it is in the written word, the visual arts, or, in this case, organized sound as music.

The term "Tuareg" is used in broad brush for peoples from five distinct confederations in the region encompassed by the African nations of Mali, Libya, Burkina Faso, Niger and Algeria with a focus on this recording on the Hoggar who live in the mountains of that name in Algeria.

This 1994 release is from the French label Chant du Monde and this is particularly striking in that Algeria was a French colony and only gained its independence in 1962 after a particularly brutal war of liberation. During this time, the Hoggar were grievously affected by the strife and, as the informative liners, note "the camel-drivers' songs, the flute and the fiddle are disappearing," a phenomenon that is sadly too common throughout the world.

Among the really impressive elements of this are the hypnotic hand-claps that accompany polyphonal singing and chanting in large group ensembles—the vocals can be haunting and otherwordly. The solo work of flutes and fiddles is also very interesting to hear, along with the teherdent, a lute-like instrument with great resonance that gives what seems like a blues feel to the performances.

Recordings like this really gives a different perspective on what music means as an everyday practice for people who are not professionals in the Western sense and it seems to this listener to get to the very marrow of what music is. Sometimes, a return to the essence is a way to recalibrate, whether it is in the written word, the visual arts, or, in this case, organized sound as music.

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

George Russell Sextet: Ezz-Thetics

George Russell is better known to jazz musicians through his highly influential treatise on modal approaches to jazz, the fearsomely titled The Lydian Chromiatic Concept of Tonal Organization and published in 1953. Russell, for example, had a significant impact on the approaches of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, among many others,

A pianist, Russell, made many records over his career, but never had the sales or critical recognition of the big names in jazz, though he made some really great records. Ezz-thetics, released in 1961 on Riverside Records, run by critic Orrin Keepnews, is especially great with Russell and band performing three originals, a contribution by band member, trombonist Dave Baker, and covers of Davis's "Nardis" and the classic "'Round Midnight" by Thelonious Monk.

As with many Russell pieces and recordings, the rhythm section really hews to keeping the bottom line and time moving crisply, often without a great deal of variation from Russell, bassist Stephen Swallow or drummer Joe Hunt, though all perform with great precision and Hunt's fills in the call-and-response section of the title piece are impressive.

The soloists include Baker, who does a particularly fine job on the brilliant title track, trumpeter Don Ellis, who plays with a crystalline and agile sound, and the always stunning Eric Dolphy. As beautfully as Baker and Ellis play, when Dolphy launches in, as is so often the case, it's like he was from years in the future (much as like Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Coltrane, or Cecil Taylor could make that kind of impact.)

In fact, Dolphy's fearless flights of improvised innovation is a perfect foil for the rest of the band given Russell's creative approaches to modal composition, and he does seem to inspire the other soloists with his staggering work. But, Ezz-thetics is a tremendous ensemble work, guided by the sure hand of a vastly underappreciated master in George Russell.

A pianist, Russell, made many records over his career, but never had the sales or critical recognition of the big names in jazz, though he made some really great records. Ezz-thetics, released in 1961 on Riverside Records, run by critic Orrin Keepnews, is especially great with Russell and band performing three originals, a contribution by band member, trombonist Dave Baker, and covers of Davis's "Nardis" and the classic "'Round Midnight" by Thelonious Monk.

As with many Russell pieces and recordings, the rhythm section really hews to keeping the bottom line and time moving crisply, often without a great deal of variation from Russell, bassist Stephen Swallow or drummer Joe Hunt, though all perform with great precision and Hunt's fills in the call-and-response section of the title piece are impressive.

The soloists include Baker, who does a particularly fine job on the brilliant title track, trumpeter Don Ellis, who plays with a crystalline and agile sound, and the always stunning Eric Dolphy. As beautfully as Baker and Ellis play, when Dolphy launches in, as is so often the case, it's like he was from years in the future (much as like Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Coltrane, or Cecil Taylor could make that kind of impact.)

In fact, Dolphy's fearless flights of improvised innovation is a perfect foil for the rest of the band given Russell's creative approaches to modal composition, and he does seem to inspire the other soloists with his staggering work. But, Ezz-thetics is a tremendous ensemble work, guided by the sure hand of a vastly underappreciated master in George Russell.

Cocteau Twins: Head Over Heels