This amazing collective of St. Louis-bred musicians recorded their third album, and second release with the Italian Black Saint label, in March 1980. The eight pieces, with contributions from all four members, display their dazzling dexterity, strong sense of rhythm, complex harmonic interplay, and daring approaches to composition to great effect.

Over time, altoist and tenorist Julius Hemphill received more attention for his songwriting and it is true that his remarkable gift for creating compelling and complicated pieces were on full display with tracks like "Connections" and "Pillars Latino." A centerpiece of this recording is the four-part suite, "Suite Music" by Hamiet Bluiett. Lake's "Sound Light" is also highly effective, as is Murray's closer, "Fast Life."

Really, though, what made this great group so memorable was their mesmerizing way of melding their talents on several instruments, including clarinets, along with the range of saxes, to develop highly original approaches to saxophone-based music that didn't need standard rhythm instruments (piano, bass, drums.)

It took a real sense of synergy, a downshift of ego, and a commitment to truel collaboration that made the World Saxophone Quartet a truly special ensemble. W.S.Q. is an especially strong release from one of the finest jazz groups of the 70s and 80s.

No criticism, no reviews, no file sharing, just appreciation, on the basic premise that music is organized sound and from there comes a journey through one listener's library. Thanks for stopping in and hope you enjoy!

Monday, August 31, 2015

Thursday, August 20, 2015

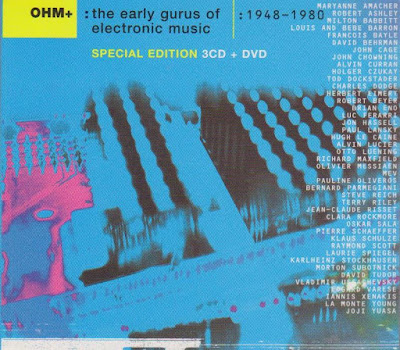

Ohm+: The Early Gurus of Electronic Music (Special Edition)

While the Ellipsis Arts label was best known for its "new age" and "world music" releases during its 1990s heyday, it did issue, in 2005, an interesting and notable triple-disc, with a bonus DVD, anthology, Ohm: The Early Gurus of Electronic Music. Bad puns aside, this is an impressive collection spanning pre-1980s performances mainly from the so-called "classical" world, though there are contributions from some composers outside of that generalized genre.

There is quite an array of composers represented here, from well-known figures like John Cage, Terry Riley, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Steve Reich, La Monte Young, Milton Babbitt, Edgard Varese, Olivier Messiaen to lesser-known, but important, pioneers like Pauline Oliveros, Alvin Lucier, the MEV collective, Morton Subotnick, Pierre Schaeffer, Luc Ferrari, and those outside "classical" and academic circles like Holger Czukay, Kalus Schulze, and Brian Eno. Even the inclusion of a 1999 version of Reich's "Pendulum Music," in which suspended microphones are swung in pendulum movements to generate sound, by noise-rock legends Sonic Youth is something of a bridge between "serious music" and the pop-rock world.

Obviously, music like this is going to have a polarizing effect on most people, a great many of whom would find this unlistenable noise. There is, however, a range of material with some pieces moving more towards some form of accessibility than others. For example, the haunting excerpt from Tchaikovsky's "Valse Sentimentale" pairs piano with the strange and wonderful sounds of the theremin, as played by its greatest exponent, Clara Rockmore.

Messiaen's "Orasion" is also other-worldly, with its "ondes martenot,"a keyboard that provides pitch changes through a ribbon and a ring, and which is also linked to traditional music. Babbitt's "Philomel" blends the human voice with the electronics in an appealing way. Oliveros's stunning "Bye Bye Butterfly" skillfully wends excerpts from "Madama Butterfly" into her improvised electronic stew.

Subotnick's "Silver Apples of the Moon" had the distinction of being the first commissioned work by a major label, Nonesuch in this case, for an electronic composition. Riley's looped piece "Poppy Nogood" [really, "Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band"] is an amazing work using soprano saxophone, inspired by the great John Coltrane, and organ to develop a time-lag effect with a patch cord.

Czukay's mesmerizing "Boat-Woman Song" has medieval choral singing with the over-dubbed samples of simple and haunting folk singing to give it a highly memorable effect. Paul Lansky's computer-generated "Six Fantasies on a Poem by Thomas Campion" has a warm and enveloping sounds of vocalizations of the poetic works that is quite beautiful. Another computer-geneated piece, Laurie Spiegel's "Applachian Grove I" has a quiet, ambient approach to creating something that has melodic associations.

Alvin Curran's "Canti Illuminati," one of the longer excerpts, is a fascinating aural experience with a sequencer, a VCS3 (used by some "progressive" rock groups in the early 70s) and the addition of bass tones and the addition of falsetto vocalizations at the end softens the electronics. Lucier's unplanned excursion "Music on a Long Thin Wire" has a droning, ambient quality that builds off a tuning from an oscillator and seems like a possible precursor to so-called "isolationist" electronic music.

Hassell's "Before and After Charm (La Notte)" has an eerie and compelling repetition of percussive sound accompanying keyboard drones in varying tones and his highly effective in giving an "Eastern" vibe, thanks to the composer's interest in Indian music. Finally, Eno's "Unfamiliar Wind (Leeks Hills)" is a characteristiclly understated, yet warm, ambient piece that closes out the CD portion nicely.

The DVD is a great bonus, especially the filmed footage of performances and interviews, including one with Rockmore talking with her sister, nephew and Robert Moog, inventor of the (in)famous synthesizer, about her work with the theremin and its inventor, as well as a snippet of a performance with her and her sister pianist. A great, though very short, clip of Paul Lansky being shown how to play the eerie instrument by an aged Leon Theremin in the latter's Moscow apartment in the waning days of teh Soviet Union is remarkable.

Milton Babbitt gives an entertaining and informative 1987 interview about his early associations with experimental electronic music, including the Mark I and II synthesizers. A lengthy performance on film from Lucier dating to 1965 is of his incredible "Music for Solo Performer." Here, Lucier is hooked by electrodes to several types of percussion, including a trash can, and uses his brainwaves to send waves in varying speeds and energy to play the percussion instruments.

A 2005 performance of "Bye Bye Butterfly" by Oliveros with visualizartions by Tony Martin is also something to behold--gorgeous musical conception with a visual accompaniment that fully supports the performance.

Finally, there is a six-minute segment from a documentary on Robert Moog, to whom the DVD is dedicated and who died in 2005, just prior to the release of the special edition. This interview with Moog about his creation is an excellent capstone to a superb anthology (provided that the listener has any inclination towards electronic music to begin with, that is.)

One last word about the package: Ellipsis Arts outdid itself (and it was at the end of its tether at the time) with a beautiful box for the discs in a clear plastic sleeve, while the 112-page booklet is chock full of commentary by the composers and others about the excepted pieces and a wealth of great photos. It really is a work of art that fully complements and serves the amazing sounds found on the four discs.

There is quite an array of composers represented here, from well-known figures like John Cage, Terry Riley, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Steve Reich, La Monte Young, Milton Babbitt, Edgard Varese, Olivier Messiaen to lesser-known, but important, pioneers like Pauline Oliveros, Alvin Lucier, the MEV collective, Morton Subotnick, Pierre Schaeffer, Luc Ferrari, and those outside "classical" and academic circles like Holger Czukay, Kalus Schulze, and Brian Eno. Even the inclusion of a 1999 version of Reich's "Pendulum Music," in which suspended microphones are swung in pendulum movements to generate sound, by noise-rock legends Sonic Youth is something of a bridge between "serious music" and the pop-rock world.

Obviously, music like this is going to have a polarizing effect on most people, a great many of whom would find this unlistenable noise. There is, however, a range of material with some pieces moving more towards some form of accessibility than others. For example, the haunting excerpt from Tchaikovsky's "Valse Sentimentale" pairs piano with the strange and wonderful sounds of the theremin, as played by its greatest exponent, Clara Rockmore.

Messiaen's "Orasion" is also other-worldly, with its "ondes martenot,"a keyboard that provides pitch changes through a ribbon and a ring, and which is also linked to traditional music. Babbitt's "Philomel" blends the human voice with the electronics in an appealing way. Oliveros's stunning "Bye Bye Butterfly" skillfully wends excerpts from "Madama Butterfly" into her improvised electronic stew.

Subotnick's "Silver Apples of the Moon" had the distinction of being the first commissioned work by a major label, Nonesuch in this case, for an electronic composition. Riley's looped piece "Poppy Nogood" [really, "Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band"] is an amazing work using soprano saxophone, inspired by the great John Coltrane, and organ to develop a time-lag effect with a patch cord.

Czukay's mesmerizing "Boat-Woman Song" has medieval choral singing with the over-dubbed samples of simple and haunting folk singing to give it a highly memorable effect. Paul Lansky's computer-generated "Six Fantasies on a Poem by Thomas Campion" has a warm and enveloping sounds of vocalizations of the poetic works that is quite beautiful. Another computer-geneated piece, Laurie Spiegel's "Applachian Grove I" has a quiet, ambient approach to creating something that has melodic associations.

Alvin Curran's "Canti Illuminati," one of the longer excerpts, is a fascinating aural experience with a sequencer, a VCS3 (used by some "progressive" rock groups in the early 70s) and the addition of bass tones and the addition of falsetto vocalizations at the end softens the electronics. Lucier's unplanned excursion "Music on a Long Thin Wire" has a droning, ambient quality that builds off a tuning from an oscillator and seems like a possible precursor to so-called "isolationist" electronic music.

Hassell's "Before and After Charm (La Notte)" has an eerie and compelling repetition of percussive sound accompanying keyboard drones in varying tones and his highly effective in giving an "Eastern" vibe, thanks to the composer's interest in Indian music. Finally, Eno's "Unfamiliar Wind (Leeks Hills)" is a characteristiclly understated, yet warm, ambient piece that closes out the CD portion nicely.

The DVD is a great bonus, especially the filmed footage of performances and interviews, including one with Rockmore talking with her sister, nephew and Robert Moog, inventor of the (in)famous synthesizer, about her work with the theremin and its inventor, as well as a snippet of a performance with her and her sister pianist. A great, though very short, clip of Paul Lansky being shown how to play the eerie instrument by an aged Leon Theremin in the latter's Moscow apartment in the waning days of teh Soviet Union is remarkable.

Milton Babbitt gives an entertaining and informative 1987 interview about his early associations with experimental electronic music, including the Mark I and II synthesizers. A lengthy performance on film from Lucier dating to 1965 is of his incredible "Music for Solo Performer." Here, Lucier is hooked by electrodes to several types of percussion, including a trash can, and uses his brainwaves to send waves in varying speeds and energy to play the percussion instruments.

A 2005 performance of "Bye Bye Butterfly" by Oliveros with visualizartions by Tony Martin is also something to behold--gorgeous musical conception with a visual accompaniment that fully supports the performance.

Finally, there is a six-minute segment from a documentary on Robert Moog, to whom the DVD is dedicated and who died in 2005, just prior to the release of the special edition. This interview with Moog about his creation is an excellent capstone to a superb anthology (provided that the listener has any inclination towards electronic music to begin with, that is.)

One last word about the package: Ellipsis Arts outdid itself (and it was at the end of its tether at the time) with a beautiful box for the discs in a clear plastic sleeve, while the 112-page booklet is chock full of commentary by the composers and others about the excepted pieces and a wealth of great photos. It really is a work of art that fully complements and serves the amazing sounds found on the four discs.

Monday, August 17, 2015

The Hugo Masters: An Anthology of Chinese Classical Music, Volume 1

In 1992, the Tucson-based Celestial Harmonies label (yes, it does sound very "new age") issued a 4-disc anthology of Chinese classical music from the Hong Kong HUGO label called "The Hugo Masters." Each disc focused on a classification of instrumentation, with the first dealing with bowed strings, the second with plucked strings, the third with wind instruments and the last installement concerning percussion.

The first disc is 67 minutes of amazing music from thirteen tracks with top-flight musicianship and virtuosity, as well as remarkable production and sound from the HUGO label, founded by Aik Yew-goh, who was a musician, engineer and producer. Their release through Celestial Harmonies marked the first time this music had been heard outside of Hong Kong.

By "bowed strings," what is meant for this recording is various forms of lutes accompanied by percussion, plucked strings and others. Some of it is vigorous and lively, others contemplative and plaintive, with strength and sensitivity often going hand-in-hand or leading from one to the other.

Chinese music often reflects beloved stories and tales from history and one can imagine, even without knowing the details of the narratives, how the music is composed to accompany the tales. As importantly, the music often features imitative qualities, in which instruments are played to mimic human conversations, the sounds of animals, and natural features like the wind or flowing of water. Human emotion is put forward in interesting ways, as well, reflecting martial qualities, pensive attitudes, cheerfulness, sadness and others.

As noted above, the playing is very impressive and the recording quality is top-notch. HUGO and Celestial Harmonies created a memorable and very affecting package that gives a brief glimpse into the rich history of Chinese classical music.

The first disc is 67 minutes of amazing music from thirteen tracks with top-flight musicianship and virtuosity, as well as remarkable production and sound from the HUGO label, founded by Aik Yew-goh, who was a musician, engineer and producer. Their release through Celestial Harmonies marked the first time this music had been heard outside of Hong Kong.

By "bowed strings," what is meant for this recording is various forms of lutes accompanied by percussion, plucked strings and others. Some of it is vigorous and lively, others contemplative and plaintive, with strength and sensitivity often going hand-in-hand or leading from one to the other.

Chinese music often reflects beloved stories and tales from history and one can imagine, even without knowing the details of the narratives, how the music is composed to accompany the tales. As importantly, the music often features imitative qualities, in which instruments are played to mimic human conversations, the sounds of animals, and natural features like the wind or flowing of water. Human emotion is put forward in interesting ways, as well, reflecting martial qualities, pensive attitudes, cheerfulness, sadness and others.

As noted above, the playing is very impressive and the recording quality is top-notch. HUGO and Celestial Harmonies created a memorable and very affecting package that gives a brief glimpse into the rich history of Chinese classical music.

Wednesday, August 5, 2015

The Mars Volta: Frances the Mute

Virtuosic guitar, dexterous drumming, classic organ, high-pitched rock screaming, usually- incomprehensible lyrics, sometimes in Spanish--these and other aspects made The Mars Volta one of the most interesting groups of the 2000s and one of the few rock bands this blogger has listened to over the last twenty-five years.

It is a mash up of instruments, styles, and sounds that could easily be judged as excessive, chaotic, strange and confounding--but that can all be said in a good way. The ambition of the group's leaders, guitarist Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and lyricist and vocalist Cedric Bixler-Zavala, is such that, even if some of the pieces are lengthy, the experimental sounds bizarre, and the lyrics strangely impressionistic, their ability to create a fascinating melange of sonic experiences is without question. And, there are times when this band is so tight, powerful, propulsive and precise that their peak moments are sheer exhilaration.

The band's second album Frances the Mute is, in some ways, an expansion of the sonic palette develolped on the debut De-Loused in the Comatorium. Suites, electronic interludes, abrupt shifts in time signatures, quiet passages exploding into intense and rapid sections, squalling guitar solos, and Bixler-Zavala's keening singing and visceral wordplay are all given greater expression. Latin rhythms and percussion, mournful trumpet solos, multi-tracking vocal harmony, and other effects broaden and deepen the rich stew of sounds that abound on the album.

The lyrics are printed on the multiple panels of the insert with striking photos that defy explanation, so it may or may not be helpful to be able to sing along with words that aren't really understandable (same for the titles and subtitles), though bits of meaning might be teased out.

It's really the melange of sounds that are something to behold and this is where Rodriguez-Lopez comes off as a Svengali with a pretty rare gift for pulling directly from punk, metal, Latin music and other styles but in a highly-personalized fashion.

The band including drummer Jon Theodore, bassist Juan Alderete de la Peña, keyboardist Isaiah Ikey Owens and percussionist and keyboardist Marcel Rodriguez-Lopez is top-notch and they were joined by a host of guests including John Frusciante of Red Hot Chili Peppers tearing off some great guitar solos of "L'Via L'Viaquez", his bandmate Flea performing on his original instrument, the trumpet (rather than the bass that he is known for), and a slew of violinists, trumpeters, horn players and other musicians.

De-Loused was exciting because it was new and heralded the arrival of a duo and band with tremendous talent. Frances may be excessive, but spectacularly so and the conception seems more assured and tied together. While the rest of The Mars Volta's catalog features a lot of higlights, this album is, to this listener, the peak. But, the remainder of the group's output will be covered here, because it was all interesting, if not quite at the level of the amazing (and confounding) Frances the Mute.

Friday, July 31, 2015

Keith Jarrett, Gary Peacock, Jack DeJohnette: Inside Out

This trio of master musicians has been playing together so long and with such amazing telepathy through a long series of recordings of standards that have received much acclaim and popularity. Not so common among their work are totally improvised performances, which is interesting given that they were all young lions in the 1960s when so-called "free jazz" was ascendant.

In the case of Peacock, he was at the apex of that wild era through his work with Albert Ayler on such seminal recordings as Spiritual Unity. DeJohnette may best be remembered for his youthful exuberance (and proficiency) with Miles Davis in the very late 60s and early 70s--part of this time working in that band with Jarrett. The leader came up as an astounding prodigy with Charles Lloyd before striking out on his own (excepting his short stint playing electric keyboards for Davis.)

As mature musicians knowing how to use their technical virtuosity in more subtle ways, the trio has justly become famed for their interpretation of pop standards. With Inside Out, however, which was recorded in London in late July 2000, there was a total reliance on improvisation. But, instead of speed, dexterity, and power, the music here is filled with Jarrett's lighter touch, Peacock's uncanny way of anchoring the band with his steady pulse, and DeJohnette's understated but complete use of his kit.

There is no screaming, pounding and displays of dazzling technique. What is present is a trio that has learned over years to listen to each other and then respond in a manner that is inventive, creative, spontaneous, yet still harmonically rich, tonally centered, and able to swing and employ melody while remaining "free."

Well, there is one fantastic exception: an encore rendition of "When I Fall in Love" that is just exquisite. Performed with great tenderness, aplomb and feeling, this piece is an excellent way to conclude the recording.

It is also notable that this is one of many recordings where the three musicians are named singly as the artists, rather than as the Keith Jarrett Trio. This seems to be a recognition of equity on Jarrett's part. He is the bigger name and the record was issued by his label, ECM, but this is a shining example of true group synchronicity. The trio issued another recording, a double disc set, of live fully improvised pieces in the excellent Always Let Me Go, as well.

Jarrett's liners are very clear: the reason for the title was to take the process of making music and turning it "inside out." This was done when the pianist suggested to his cohorts that, if their sound check renditions of existing material did not measure up, then they would go completely improvised. So, the two nights recorded in London turned out to be just that.

Being "attentive" and "in tune" with each other, Jarrett went on, were even more imperative than before and he takes a quick dig at Wynton Marsalis and Ken Burns (whose television series on jazz had just been issued) over what constitutes "free" playing--and it is true that Marsalis, Burns and company gave short shrift to most "free jazz". Yet, there is plenty of harmony, melody and structure in the improvisation, so it might be seen as a more mature form of free playing.

But, as Jarrett concludes, there is a great deal of blues feeling expressed on this album and he wrote that "sometimes we live the blues even when we're free of the blues." It might be free, but it's not absent of accessibility, even within a totally improvised format. Inside Out is a departure from the usual body of work of this great trio, but their approach to working in synthesis is fundamentally unchanged, which makes this album so stellar.

In the case of Peacock, he was at the apex of that wild era through his work with Albert Ayler on such seminal recordings as Spiritual Unity. DeJohnette may best be remembered for his youthful exuberance (and proficiency) with Miles Davis in the very late 60s and early 70s--part of this time working in that band with Jarrett. The leader came up as an astounding prodigy with Charles Lloyd before striking out on his own (excepting his short stint playing electric keyboards for Davis.)

As mature musicians knowing how to use their technical virtuosity in more subtle ways, the trio has justly become famed for their interpretation of pop standards. With Inside Out, however, which was recorded in London in late July 2000, there was a total reliance on improvisation. But, instead of speed, dexterity, and power, the music here is filled with Jarrett's lighter touch, Peacock's uncanny way of anchoring the band with his steady pulse, and DeJohnette's understated but complete use of his kit.

There is no screaming, pounding and displays of dazzling technique. What is present is a trio that has learned over years to listen to each other and then respond in a manner that is inventive, creative, spontaneous, yet still harmonically rich, tonally centered, and able to swing and employ melody while remaining "free."

Well, there is one fantastic exception: an encore rendition of "When I Fall in Love" that is just exquisite. Performed with great tenderness, aplomb and feeling, this piece is an excellent way to conclude the recording.

It is also notable that this is one of many recordings where the three musicians are named singly as the artists, rather than as the Keith Jarrett Trio. This seems to be a recognition of equity on Jarrett's part. He is the bigger name and the record was issued by his label, ECM, but this is a shining example of true group synchronicity. The trio issued another recording, a double disc set, of live fully improvised pieces in the excellent Always Let Me Go, as well.

Jarrett's liners are very clear: the reason for the title was to take the process of making music and turning it "inside out." This was done when the pianist suggested to his cohorts that, if their sound check renditions of existing material did not measure up, then they would go completely improvised. So, the two nights recorded in London turned out to be just that.

Being "attentive" and "in tune" with each other, Jarrett went on, were even more imperative than before and he takes a quick dig at Wynton Marsalis and Ken Burns (whose television series on jazz had just been issued) over what constitutes "free" playing--and it is true that Marsalis, Burns and company gave short shrift to most "free jazz". Yet, there is plenty of harmony, melody and structure in the improvisation, so it might be seen as a more mature form of free playing.

But, as Jarrett concludes, there is a great deal of blues feeling expressed on this album and he wrote that "sometimes we live the blues even when we're free of the blues." It might be free, but it's not absent of accessibility, even within a totally improvised format. Inside Out is a departure from the usual body of work of this great trio, but their approach to working in synthesis is fundamentally unchanged, which makes this album so stellar.

Labels:

ECM,

free jazz,

Gary Peacock,

Inside Out,

Jack deJohnette,

jazz,

Keith Jarrett

Monday, July 27, 2015

Franz Joseph Haydn: String Quartets, Op. 64, #s4-6

From the late 1980s on the German budget label, Pilz, comes this fine recording of three of Haydn's best-known string quartets, filled with gorgeous melody, rich harmony and excellent playing by the Caspa da Salo Quartet.

Composed in 1790 and often called the Tost quartets after Johann Tost, a Hungarian violinist who assisted the composer in finding a publisher for much of his work and who is given a dedication by Haydn for the Op. 64 works, this trio includes the fifth, called the "Lark Quartet", and which is one of the most famous of his pieces.

All six of the set are remarkable works. The quality of these pieces reflect Haydn's full development, by his sixties, of both the string quartet and the symphony genres.

They were also written just as the maestro was ending a decades-long employment at the Esterhazy court and soon to be sent to London, where he reached new levels of fame with some of his late symphonies.

When it comes to bargain-basement budget classical labels, Pilz is probably the most notable of all. This blogger has hundreds and hundreds of classical recordings, many on high-end labels, and quite a few on Naxos, Pilz and other budget ones, and does not have any pretension as to knowledge or deep understanding of the technical underpinnings of the music. But, this recording and the few dozen others from Pilz are enjoyable.

Click here an interesting take on what the Pilz series has to offer for the "frugal" classical music consumer--this was definitely relatable!

Composed in 1790 and often called the Tost quartets after Johann Tost, a Hungarian violinist who assisted the composer in finding a publisher for much of his work and who is given a dedication by Haydn for the Op. 64 works, this trio includes the fifth, called the "Lark Quartet", and which is one of the most famous of his pieces.

All six of the set are remarkable works. The quality of these pieces reflect Haydn's full development, by his sixties, of both the string quartet and the symphony genres.

They were also written just as the maestro was ending a decades-long employment at the Esterhazy court and soon to be sent to London, where he reached new levels of fame with some of his late symphonies.

When it comes to bargain-basement budget classical labels, Pilz is probably the most notable of all. This blogger has hundreds and hundreds of classical recordings, many on high-end labels, and quite a few on Naxos, Pilz and other budget ones, and does not have any pretension as to knowledge or deep understanding of the technical underpinnings of the music. But, this recording and the few dozen others from Pilz are enjoyable.

Click here an interesting take on what the Pilz series has to offer for the "frugal" classical music consumer--this was definitely relatable!

Monday, July 20, 2015

Alhaji Bai Konte: Kora Melodies from The Gambia

This was another memorable purchase in the early Nineties as explorations in "world music" were beginning and it was the first introduction, outside of an abridged piece on a JVC sampler CD, to the amazing and rich sound of the kora.

The 21-stringed gourd-like instrument has so much range and complexity and, in the hands of a master griot like Bai Konte, it takes on an otherworldly quality to it. Beautiful melodies, deft arpeggios, and an assured technique mark this 1973 recording, released to coincide with Bai Konte's first tour of the United States and released by Rounder Records.

Then a three-year old company, Rounder was becoming well-known for its releases of folk, bluegrass and other American forms of music, but the beauty of this music inspired the label to issue the album because it seemed to relate in spirit to the rest of Rounder's expanding catalog.

The 1990s purchase of the album was on cassette, so the great thing about the CD version is the presence of four extra tracks, three of them recorded at a college concert in Pennsylvania. The remainder of the album was recorded in The Gambia, including one of the bonus tracks which was taped at a performance in the town of Sinanor.

Most of the insert is about the sights and sounds encountered when the producers spent time with Bai Konte in The Gambia and give some idea of the important of Islam, Gambian traditions, and family in the musical world of the kora master.

After this first foray into world music, Rounder later released over fifty volumes of the remarkable "Anthology of World Music" series. More selections from that series to come soon!

The 21-stringed gourd-like instrument has so much range and complexity and, in the hands of a master griot like Bai Konte, it takes on an otherworldly quality to it. Beautiful melodies, deft arpeggios, and an assured technique mark this 1973 recording, released to coincide with Bai Konte's first tour of the United States and released by Rounder Records.

Then a three-year old company, Rounder was becoming well-known for its releases of folk, bluegrass and other American forms of music, but the beauty of this music inspired the label to issue the album because it seemed to relate in spirit to the rest of Rounder's expanding catalog.

The 1990s purchase of the album was on cassette, so the great thing about the CD version is the presence of four extra tracks, three of them recorded at a college concert in Pennsylvania. The remainder of the album was recorded in The Gambia, including one of the bonus tracks which was taped at a performance in the town of Sinanor.

Most of the insert is about the sights and sounds encountered when the producers spent time with Bai Konte in The Gambia and give some idea of the important of Islam, Gambian traditions, and family in the musical world of the kora master.

After this first foray into world music, Rounder later released over fifty volumes of the remarkable "Anthology of World Music" series. More selections from that series to come soon!

Thursday, July 16, 2015

The Durutti Column: The Guitar and Other Machines

This was an album bought new on cassette when issued in 1987 and it was striking how different much of the sound was compared to earlier records.

For one thing, even though drum machines had been used on the first Durutti Column record, The Return of the Durutti Column (1979), there was an increasing use of electronics for The Guitar and Other Machines, as discussed in the liner notes of the expanded album version released under the Factory Once iteration of Anthony Wilson's Factory Records label.

In his typically breezy and idiosyncratic style of writing, Wilson observed that "Vini had some new technology thrust upon him" in the form of a Yamaha sequencer and a DMX drum machine. With these new tools, the guitarist created a recording that featured much of his gorgeous guitar, as well as keyboards (he was first a pianist) and which was augmented with drums, xylophone and the drum machine by longtime compatriot and manager Bruce Mitchell, violist John Metcalfe and guests Stephen Street, who played bass on one track as well as produced the album, Rob Gray, provider of mouth organ on two tracks, and vocalists Stanton Miranda and Pol. Tim Kellet, who had been in the band but left to join Simply Red, contributes a good trumpet solo on "When the World."

The other major change was that, while there was plenty of the precise and atmospheric guitar playing that has distinguised Reilly from anyone else emerging from the postpunk era, The Guitar and Other Machines features some examples of performance that are more "rock" like. The most amazing result was the absolutely scorching guitar solo from "When the World." There are similar sounds on "Arpeggiator," as well.

Finally, there is Stephen Street's production. He had produced Morrissey's Viva Hate, which Reilly, who had been in a short-lived punk band with Morrissey in the late 1970s, performed on, so the partnership here appears to have meant a more direct and, perhaps, accessible sound. This is a good thing, actually, as the opening up of the sound takes Reilly out of a more confined environment without sacrificing any of his aesthetic.

What is rather typical, though fantastically so, is the way that Reilly and his collaborators blend instrumentation, creates evocative emotional sounds, and makes his work so personalized. A beautiful piece like "Jongleur Gray" with Reilly's guitar and piano juxtaposed with Gray's harmonica is then followed by :When the World" which begins with drum machines, Reilly's rhythm guitar, and a distant harmonica before the vocals from Miranda come in. Suddenly, the uncharacteristically searing guitar blasts through the piece, changing the atmosphere substantially and in a thrilling way.

After that is the sublime "U.S.P." which is a feature for Reilly's fantastic acoustic guitar playing--something that hasn't been heard often enough for this admirer. Then, on the excellent "Bordeaux Sequence" more drum machines and electronic keyboards lead into some plucked viola from Metcalfe before Pol's beguiling vocals take the piece somewhere else.

Following is the beautiful "Pol in B," following a long tradition of Reilly's in naming pieces for those close to him. The extraordinary lead is echoed by pretty acoustic flourishes and keyboard touches--yet another example of his unique penchant for creating some of the most striking mood music.

These examples show how the diversity and the sequencing of the pieces make The Guitar and Other Machines a highlight in the long and extraordinary career of one of the most interesting musicians around.

There are four bonus pieces known as "Related Works" in the Factory Once reissue series, including "Don't Think Your Funny" which provides Vini's oft-maligned vocals with a backing vocal layered behind and is another simple and effective little piece at under two minutes. The unusual use of bongos and sampled audio make "Dream Topping" and "You Won't Feel Out of Place" distinctive for the DC discography. "28 Oldham Street" has a rhythmic keyboard pattern under Reilly's trebly work on his guitar, while drum machines come a bit in to the piece, making for a nice piece.

On the CD insert, there is reference to four other pieces from a performance at Peter Gabriel's WOMAD festival in 1989, but this must've been for a UK version, because the one discussed here lacks these tracks. These can be heard elsewhere, notably on the 1989 album Vini Reilly, as well as 1991's Dry collection, and include the incredible "Otis," a sampling of soul singer Otis Redding's voice with one of Reilly's most memorable guitar lines.

For one thing, even though drum machines had been used on the first Durutti Column record, The Return of the Durutti Column (1979), there was an increasing use of electronics for The Guitar and Other Machines, as discussed in the liner notes of the expanded album version released under the Factory Once iteration of Anthony Wilson's Factory Records label.

In his typically breezy and idiosyncratic style of writing, Wilson observed that "Vini had some new technology thrust upon him" in the form of a Yamaha sequencer and a DMX drum machine. With these new tools, the guitarist created a recording that featured much of his gorgeous guitar, as well as keyboards (he was first a pianist) and which was augmented with drums, xylophone and the drum machine by longtime compatriot and manager Bruce Mitchell, violist John Metcalfe and guests Stephen Street, who played bass on one track as well as produced the album, Rob Gray, provider of mouth organ on two tracks, and vocalists Stanton Miranda and Pol. Tim Kellet, who had been in the band but left to join Simply Red, contributes a good trumpet solo on "When the World."

The other major change was that, while there was plenty of the precise and atmospheric guitar playing that has distinguised Reilly from anyone else emerging from the postpunk era, The Guitar and Other Machines features some examples of performance that are more "rock" like. The most amazing result was the absolutely scorching guitar solo from "When the World." There are similar sounds on "Arpeggiator," as well.

Finally, there is Stephen Street's production. He had produced Morrissey's Viva Hate, which Reilly, who had been in a short-lived punk band with Morrissey in the late 1970s, performed on, so the partnership here appears to have meant a more direct and, perhaps, accessible sound. This is a good thing, actually, as the opening up of the sound takes Reilly out of a more confined environment without sacrificing any of his aesthetic.

What is rather typical, though fantastically so, is the way that Reilly and his collaborators blend instrumentation, creates evocative emotional sounds, and makes his work so personalized. A beautiful piece like "Jongleur Gray" with Reilly's guitar and piano juxtaposed with Gray's harmonica is then followed by :When the World" which begins with drum machines, Reilly's rhythm guitar, and a distant harmonica before the vocals from Miranda come in. Suddenly, the uncharacteristically searing guitar blasts through the piece, changing the atmosphere substantially and in a thrilling way.

After that is the sublime "U.S.P." which is a feature for Reilly's fantastic acoustic guitar playing--something that hasn't been heard often enough for this admirer. Then, on the excellent "Bordeaux Sequence" more drum machines and electronic keyboards lead into some plucked viola from Metcalfe before Pol's beguiling vocals take the piece somewhere else.

Following is the beautiful "Pol in B," following a long tradition of Reilly's in naming pieces for those close to him. The extraordinary lead is echoed by pretty acoustic flourishes and keyboard touches--yet another example of his unique penchant for creating some of the most striking mood music.

These examples show how the diversity and the sequencing of the pieces make The Guitar and Other Machines a highlight in the long and extraordinary career of one of the most interesting musicians around.

There are four bonus pieces known as "Related Works" in the Factory Once reissue series, including "Don't Think Your Funny" which provides Vini's oft-maligned vocals with a backing vocal layered behind and is another simple and effective little piece at under two minutes. The unusual use of bongos and sampled audio make "Dream Topping" and "You Won't Feel Out of Place" distinctive for the DC discography. "28 Oldham Street" has a rhythmic keyboard pattern under Reilly's trebly work on his guitar, while drum machines come a bit in to the piece, making for a nice piece.

On the CD insert, there is reference to four other pieces from a performance at Peter Gabriel's WOMAD festival in 1989, but this must've been for a UK version, because the one discussed here lacks these tracks. These can be heard elsewhere, notably on the 1989 album Vini Reilly, as well as 1991's Dry collection, and include the incredible "Otis," a sampling of soul singer Otis Redding's voice with one of Reilly's most memorable guitar lines.

Sunday, July 5, 2015

Miles Davis: In a Silent Way

Saxophonist Bob Belden died a few weeks back and, while he was a well-known and respected musician, he also was a contributor to some of the remarkable box sets issued by Sony/Columbia Records regarding the music of the great Miles Davis.

One of the sets in which Belden made a significant contribution concerns one of the great Davis recordings, 1969's In a Silent Way. This album marked Davis's first extensive use of electric instrumentation, but it also represented a shift in composing style and recording techniques employed by the trumpeter and his long-time producer, Teo Macero.

What is striking about this album compared to recent Davis releases with his great quintet (Hancock, Carter, Williams and Shorter) and anything else from the period is not so much that he used electric instruments, but that he created a type of sound that was more atmospheric and groove-oriented.

Bassist Dave Holland, whose dexterity, speed and power have been amply demonstrated elsewhere, plays highly repetitive lines here, but it's perfectly in service to the music Davis orchestrated. Tony Williams, whose mastery of the cymbals was exceptional, largely plays that part of his kit for the recording, excepting towards the end of the recording. Keyboardists Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul, all brilliant players, are primarily concerned with laying down the ambiance that anchors the album.

The soloists are Davis, Wayne Shorter and, getting his first major exposure in the music world, the incredible John McLaughlin on guitar. The interplay between Shorter and Davis, honed over just beyond four years of working together, is clear and precise. Hearing the two, though, with the five-man rhythm section playing the way they did, is fresh and new compared to the quintet music that preceded this record.

McLaughlin is really, however, the linchpin of this record. His guitar work is at times subtle, at other times direct, and usually inventive and unique. He expanded his sonic palette on the phenomenal Bitches Brew, along with an augmented and beefed up ensemble that Davis employed. On In a Silent Way, though, Laughlin gets more of the spotlight because of the way the sound was constructed.

Another key player is producer Teo Macero, whose uncanny way of working with Davis's methods of recording and concepts behind the music often generated some remarkable results. Macero's edits are sometimes very jarring, as is the case with side two's In a Silent Way/It's About That Time, but his work deserves praise for the creative way in which he stitched the recordings together. This process became more marked with subsequent records and it has been hotly debated whether there was merit in much of this. Clearly, though, Davis wanted Macero to work in this way and, on this record, the results are excellent.

This may not be an apt corollary, but, to this listener, there is something about this record that is akin to the Birth of the Cool recordings. It is probably more in the general sound and tempo--in which the ambiance and mid-tempo stylings are effected. Yet, the album is anything but a reference to the past, at least not directly. Instead, it is an emphatic nod (and it is subtle, like a nod--whereas Bitches Brew was a direct shake of the yead) toward the future.

Miles did what he needed to do after several years with the quintet to move his music in a different direction, but, in doing so, he incorporated the spirit of (and, often, direct connections to) rock, soul, pop and modern classical music.

In a Silent Way was an almost ambient way to chart new directions, where Bitches Brew was a powerful pathbreaking effort. They are perfect companions to show where, 20 years in as a leader, Miles was going to go next. He was called a sellout for using electric instruments and making references to popular and other forms of music. But, how can you sell out, when you're making album long sides of 20 minutes or more?

Miles wasn't selling out, he was moving on. The fact that he could do so, once again changing his style, personnel, composing, production and editing, and image and create another chapter in his career, when most of his contemporaries were still playing the same way they had done in the Forties, Fifties or early Sixties is testament to his greatness. In a Silent Way is an amazing record, somewhat overshadowed by Bitches Brew, when, perhaps, it should be seen as a precursor and direct linkage.

One of the sets in which Belden made a significant contribution concerns one of the great Davis recordings, 1969's In a Silent Way. This album marked Davis's first extensive use of electric instrumentation, but it also represented a shift in composing style and recording techniques employed by the trumpeter and his long-time producer, Teo Macero.

What is striking about this album compared to recent Davis releases with his great quintet (Hancock, Carter, Williams and Shorter) and anything else from the period is not so much that he used electric instruments, but that he created a type of sound that was more atmospheric and groove-oriented.

Bassist Dave Holland, whose dexterity, speed and power have been amply demonstrated elsewhere, plays highly repetitive lines here, but it's perfectly in service to the music Davis orchestrated. Tony Williams, whose mastery of the cymbals was exceptional, largely plays that part of his kit for the recording, excepting towards the end of the recording. Keyboardists Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul, all brilliant players, are primarily concerned with laying down the ambiance that anchors the album.

The soloists are Davis, Wayne Shorter and, getting his first major exposure in the music world, the incredible John McLaughlin on guitar. The interplay between Shorter and Davis, honed over just beyond four years of working together, is clear and precise. Hearing the two, though, with the five-man rhythm section playing the way they did, is fresh and new compared to the quintet music that preceded this record.

McLaughlin is really, however, the linchpin of this record. His guitar work is at times subtle, at other times direct, and usually inventive and unique. He expanded his sonic palette on the phenomenal Bitches Brew, along with an augmented and beefed up ensemble that Davis employed. On In a Silent Way, though, Laughlin gets more of the spotlight because of the way the sound was constructed.

Another key player is producer Teo Macero, whose uncanny way of working with Davis's methods of recording and concepts behind the music often generated some remarkable results. Macero's edits are sometimes very jarring, as is the case with side two's In a Silent Way/It's About That Time, but his work deserves praise for the creative way in which he stitched the recordings together. This process became more marked with subsequent records and it has been hotly debated whether there was merit in much of this. Clearly, though, Davis wanted Macero to work in this way and, on this record, the results are excellent.

This may not be an apt corollary, but, to this listener, there is something about this record that is akin to the Birth of the Cool recordings. It is probably more in the general sound and tempo--in which the ambiance and mid-tempo stylings are effected. Yet, the album is anything but a reference to the past, at least not directly. Instead, it is an emphatic nod (and it is subtle, like a nod--whereas Bitches Brew was a direct shake of the yead) toward the future.

Miles did what he needed to do after several years with the quintet to move his music in a different direction, but, in doing so, he incorporated the spirit of (and, often, direct connections to) rock, soul, pop and modern classical music.

In a Silent Way was an almost ambient way to chart new directions, where Bitches Brew was a powerful pathbreaking effort. They are perfect companions to show where, 20 years in as a leader, Miles was going to go next. He was called a sellout for using electric instruments and making references to popular and other forms of music. But, how can you sell out, when you're making album long sides of 20 minutes or more?

Miles wasn't selling out, he was moving on. The fact that he could do so, once again changing his style, personnel, composing, production and editing, and image and create another chapter in his career, when most of his contemporaries were still playing the same way they had done in the Forties, Fifties or early Sixties is testament to his greatness. In a Silent Way is an amazing record, somewhat overshadowed by Bitches Brew, when, perhaps, it should be seen as a precursor and direct linkage.

Sunday, June 21, 2015

Luciano Berio: Sequenzas I-XIV

This is a spellbinding and utterly absorbing three-disc set of performances, released by the Naxos label in 2006, on an array of solo instruments written by the Italian composer over a forty-four year period from 1958 until just a year prior to his death in 2003.

The lengths of the sequences run from just over five minutes for the first of the lot for flute to sequence ten on trumpet with piano resonance at just over seventeen minutes. Other instruments featured are harp, piano, trombone, viola, oboe, violin, clarinet, guitar, bassoon, accordion, cello, soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, and the female voice.

The recordings were made between 1998 and 2004 and are uniformly stunning in the composing, beautiful in the playing, and especially crystalline in the recording. In fact, the use of St. John Chrysostom Church in Newmarket, Ontario, Canada provided a very particular environment in which the sounds emanating from the instrument filled the structure and almost makes the venue another instrument with the rich timbres and sustained echo adding so much to each performance.

Of particular note is Berio's extensive use of extended techniques beyond traditional methods of performance on any given instruments. These can be done any number of ways in terms of tapping rhythms on the body of an instrument, overblowing through a mouthpiece to create multiphonic sounds, bowing or plucking strings on a different part of a fret or rethinking how an instrument is generally used (such as a harp being played more aggressively through tapping on the body as well as varied strumming.)

Perhaps the most interesting of the extended techniques comes in the aforementioned sequence ten, in which the trumpeter blows into an open piano to generate the resonance referred to in the title. Also amazing is the sequence for bassoon (twelve), in which it appears that the player is utilizing circular breathing to continue the performance all the way through--this is truly amazing to hear.

It is probably too much to attempt to listen to all three discs and fourteen sequences at one time, but with each disc running at approximately an hour, taking them individually makes for an easier digesting of the rich content of the compositions and a fuller appreciation for the playing and, again, for that venue.

This listener, very new to Berio, having only heard his vocal masterwork Coro, approached the box that way, taking each disc on its own and absorbing what was heard before moving on to the next. Also very helpful are Richard Whitehouse's liner notes, pointing out that the complexity of the composing and technical virtuosity are matched by the emotive expressiveness brought to the performances by the musicians.

Perhaps the most impressive achievement in this series, though, is the way in which Berio wrote in a modern fashion while making reference to tradition. This is not an extraordinarily difficult set of recordings to listen to--at least, not in three doses as noted above.

Someone who doesn't have a particular interest in so-called avant garde classical music, but may be willing to venture beyond traditional expressions on a variety of largely tried and true instruments, might find that taking the sequenzas in one disc at a time can be highly rewarding. This listener has even listened to these recordings in two consecutive home gym workouts, which might (or might not) mean something in terms of the power and complexity of the sounds developing a strong sense of highly creative energy.

As is so often the case, Naxos is to be commended for putting together such a gorgeously-recorded, stunningly-performed and very affordable set of this remarkable music.

The lengths of the sequences run from just over five minutes for the first of the lot for flute to sequence ten on trumpet with piano resonance at just over seventeen minutes. Other instruments featured are harp, piano, trombone, viola, oboe, violin, clarinet, guitar, bassoon, accordion, cello, soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, and the female voice.

The recordings were made between 1998 and 2004 and are uniformly stunning in the composing, beautiful in the playing, and especially crystalline in the recording. In fact, the use of St. John Chrysostom Church in Newmarket, Ontario, Canada provided a very particular environment in which the sounds emanating from the instrument filled the structure and almost makes the venue another instrument with the rich timbres and sustained echo adding so much to each performance.

Of particular note is Berio's extensive use of extended techniques beyond traditional methods of performance on any given instruments. These can be done any number of ways in terms of tapping rhythms on the body of an instrument, overblowing through a mouthpiece to create multiphonic sounds, bowing or plucking strings on a different part of a fret or rethinking how an instrument is generally used (such as a harp being played more aggressively through tapping on the body as well as varied strumming.)

Perhaps the most interesting of the extended techniques comes in the aforementioned sequence ten, in which the trumpeter blows into an open piano to generate the resonance referred to in the title. Also amazing is the sequence for bassoon (twelve), in which it appears that the player is utilizing circular breathing to continue the performance all the way through--this is truly amazing to hear.

It is probably too much to attempt to listen to all three discs and fourteen sequences at one time, but with each disc running at approximately an hour, taking them individually makes for an easier digesting of the rich content of the compositions and a fuller appreciation for the playing and, again, for that venue.

This listener, very new to Berio, having only heard his vocal masterwork Coro, approached the box that way, taking each disc on its own and absorbing what was heard before moving on to the next. Also very helpful are Richard Whitehouse's liner notes, pointing out that the complexity of the composing and technical virtuosity are matched by the emotive expressiveness brought to the performances by the musicians.

Perhaps the most impressive achievement in this series, though, is the way in which Berio wrote in a modern fashion while making reference to tradition. This is not an extraordinarily difficult set of recordings to listen to--at least, not in three doses as noted above.

Someone who doesn't have a particular interest in so-called avant garde classical music, but may be willing to venture beyond traditional expressions on a variety of largely tried and true instruments, might find that taking the sequenzas in one disc at a time can be highly rewarding. This listener has even listened to these recordings in two consecutive home gym workouts, which might (or might not) mean something in terms of the power and complexity of the sounds developing a strong sense of highly creative energy.

As is so often the case, Naxos is to be commended for putting together such a gorgeously-recorded, stunningly-performed and very affordable set of this remarkable music.

Thursday, June 18, 2015

Flamenco Live!

This 4-disc box set, issued by the British Nimbus label in 2000, is a collection of four previously-released live albums from the label. Three of the four feature singers and guitarists performing cante with the traditional-style vocals of María la Burra, María Soleá, José de la Tomasa, Chano Lobato, Manuel de Paula, Gaspar de Utrera, Miguel Funi, El Cabrero, Tina Pavón, Emilia Jandra, Rafael Calderón, Manuel Márquez, and Monica Dominguez--all of whom deserve mention because they are all excellent in conveying the passion and intensity of the form.

On two of the cante discs, the guitarists, who play with great dexterity, emotion and the use of variations are Paco del Gastor and his brother Juan. They provide a perfect accompaniment to the vocalists in the environments of flamenco clubs, with a few in larger concert settings. The fourth disc, another cante, features guitarist Manolo Dominguez, whose daughter Monica is one of the five vocalists, with the material also recorded in clubs.

The third disc is a spotlight for Paco del Gastor, whose talents took him from his native Morón de la Frontera, where much of this music was recorded and where the del Gastor dynasty of excellent guitarists were from, to the Spanish capital Madrid. After hearing three recordings of cante, in which the singers are justly at the fore, demonstrating their various talents and abilities to the fullest, it is a bit jarring to hear a solo guitar performance--at least at the beginning. But, Paco del Gastor is such an amazing performer that any sense of disconnect melts away quickly as the listener is absorbed in the work of this master.

That said, the highlight of this box, at least for this listener, are the two performances at the end of the second disc, Cante Flamenco, in which the del Gastor brothers take a back seat to the remarkable talents of El Cabrero (José Dominguez Muñoz), who had a twelve-year partnership with Paco del Gastor.

That synergy definitely shows on these pieces, recorded at a larger festival, but El Cabrero is the main attraction, with his vocals featuring a distinctive ululating at the end of certain phrases, a very strong elongating of the syllables that characterize the cante, but in a way that appears more like a plaintive and anguished cry, and politicized lyrical content.

There is a lot of material in this set, four-and-half hours worth, but most of it consists of rare instances of traditional pieces recorded in small flamenco clubs in Andalucia, the cradle of the form, and this is a paramount reason to shell out for the whole set, though the individual discs are available from Nimbus. Those who favor the guitar work over the vocals would be advised to search out the Flamenco de la Frontera disc from Paco del Gastor, or the several albums on Nimbus from Paco Peña, another giant of the flamenco guitar.

For this listener, relatively new to the music, though, the vocals seem essential in conveying the passion and intensity as reflected in the cante that is ultimately the heart and soul of flamenco.

On two of the cante discs, the guitarists, who play with great dexterity, emotion and the use of variations are Paco del Gastor and his brother Juan. They provide a perfect accompaniment to the vocalists in the environments of flamenco clubs, with a few in larger concert settings. The fourth disc, another cante, features guitarist Manolo Dominguez, whose daughter Monica is one of the five vocalists, with the material also recorded in clubs.

The third disc is a spotlight for Paco del Gastor, whose talents took him from his native Morón de la Frontera, where much of this music was recorded and where the del Gastor dynasty of excellent guitarists were from, to the Spanish capital Madrid. After hearing three recordings of cante, in which the singers are justly at the fore, demonstrating their various talents and abilities to the fullest, it is a bit jarring to hear a solo guitar performance--at least at the beginning. But, Paco del Gastor is such an amazing performer that any sense of disconnect melts away quickly as the listener is absorbed in the work of this master.

That said, the highlight of this box, at least for this listener, are the two performances at the end of the second disc, Cante Flamenco, in which the del Gastor brothers take a back seat to the remarkable talents of El Cabrero (José Dominguez Muñoz), who had a twelve-year partnership with Paco del Gastor.

That synergy definitely shows on these pieces, recorded at a larger festival, but El Cabrero is the main attraction, with his vocals featuring a distinctive ululating at the end of certain phrases, a very strong elongating of the syllables that characterize the cante, but in a way that appears more like a plaintive and anguished cry, and politicized lyrical content.

There is a lot of material in this set, four-and-half hours worth, but most of it consists of rare instances of traditional pieces recorded in small flamenco clubs in Andalucia, the cradle of the form, and this is a paramount reason to shell out for the whole set, though the individual discs are available from Nimbus. Those who favor the guitar work over the vocals would be advised to search out the Flamenco de la Frontera disc from Paco del Gastor, or the several albums on Nimbus from Paco Peña, another giant of the flamenco guitar.

For this listener, relatively new to the music, though, the vocals seem essential in conveying the passion and intensity as reflected in the cante that is ultimately the heart and soul of flamenco.

Monday, June 15, 2015

Black Uhuru: The Dub Factor

It was probably Fall 1984, not long after this blogger saw Black Uhuru open a wondrous double bill with the phenomenal King Sunny Ade, when I bought this album on vinyl. From the first listen, the recording made a huge impression because it was the first of many excursions into the heart of dub, that amazing offshoot of reggae featuring a wide palette of processed sounds injected into the instrumental mix of a song, with occasional samples of the vocals by lead singer Michael Rose and backing vocalists Puma Jones and founder Duckie Simpson.

.

When reggae shifted gears into dancehall and other genres after the mid-80s, it was years before I went and bought a CD version of this album and all of the great memories of the sonic experience flooded back. Recently, several albums of choice dub from the likes Augustus Pablo, King Tubby, Lee "Scratch" Perry and the Trojan Records label have rekindled that interest in the outer limits of reggae that dub embodies.

Black Uhuru's The Dub Factor is a reworking of tracks, largely from the great Chill Out album from 1982, which immediately preceded this dub masterpiece. A few songs, principally "Youth" and "Puffed Out" from Red's "Youth of Eglington" and "Puff She Puff" come from other sources. The 2003 remastered version adds three tracks, including takes on "Carbine" and "Journey", also from Red, a take on the title track from Chill Out called "Destination Unknown."

As great as the dubs are with the echo, reverb and other effects rendered to the instrumental backbone of these songs, as well as the disembodied vocal samples, the greatness of Black Uhuru, in addition to the excellent musicians and the preeminent Riddim Twins of Robbie Shakespeare (Basspeare) and Sly Dunbar (Drumbar), was the top-notch songwriting of Rose. He wrote so many memorable songs for the band in that first half of the 80s, when classic reggae was gradually giving way to a digital movement and Black Uhuru reigned as the supreme band in the genre after the untimely demise of Bob Marley.

In addition to the production skills of Dunbar and Shakespeare, who embraced the technological movement to electronics through syndrums and other devices, this album is testament to the skill of Paul "Groucho" Smykle, an Island Records producer, who remixed the record. Even though The Dub Factor has a crystalline sound benefiting from the latest in studio wizardry, the album delves deeply into the dub aesthetic, combining the studio sheen with a sense of audio adventure.

Following this recording, Black Uhuru issued one more album, 1985's Anthem, which won the first Grammy for a reggae album. Yet, there was a lack of passion, energy and urgency to that ultra-sleek sounding record that was a precursor to Rose leaving the group. Though there were several versions of the band over the years, Black Uhuru never again approached anywhere near the heights of its early 80s heyday. Rose was away from the scene for a time and then returned with dancehall-infused solo albums that sold decently, but were a far cry from his peak as a socially-conscious crusader. For a brief period a decade ago, Rose rejoined Black Uhuru, but it was a very brief reunion.

It's hard to believe that it has been over 30 years since that record was first heard by this blogger, but its qualities as a landmark in reggae and dub are as obvious as ever.

Friday, June 12, 2015

Ornette Coleman: Town Hall, 1962

The death of the great Ornette Coleman yesterday at age 85 means the loss of another master of creative musical expression, not just in jazz, but in all music.

This blogger has vivid memories of buying, in the same day in 1990, John Coltrane's My Favorite Things and an album of Atlantic outtakes from Coleman's years there, The Art of the Improvisors, especially its opening, frenetic "The Circle with a Hole in the Middle." That recording let quickly to purchases of such classics as The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century, Free Jazz and many others.

Coleman's approach to harmony, his melodic sense, and the total freedom given to the musicians to play what felt right, provided they were listening and responding to each other, was revolutionary, drawing scorn and appreciation across the spectrum.

While his influence wasn't such that covers of his pieces are very common, outside of a few iconic tracks like "Lonely Woman" or the rare tribute album, like John Zorn's amazing Spy vs. Spy, his legacy is perhaps best represented in the spirit of expression that the murkily-defined concept of harmolodics, in which harmony is given equal weight with melody in the context of free expression concerning time, rhythm and other structures, embodied.

Now, in 1990, this listener, new to jazz, did not appreciate much of these notions, but was drawn to the playful, celebratory, light and crisp sounds of those Atlantic recordings that were made at the peak of Coleman's notoriety.

Of course, Coleman continued to probe, explore and express through his years at Blue Note, Columbia and then on to his electric group, Prime Time, and more modern pursuits, including the remarkable Sound Grammar, the fantastic collaboration with Pat Metheny, Sound X, and the little-discussed duet with Joachim Kuhn, Colors, a rare instance of the use of piano in Coleman's music. That live recording in Leipzig from the mid-1990s represented Coleman's unceasing explorations in instrumentation, as well as sound, and may have had a precursor from over thirty years before.

This was the Town Hall concert of 21 December 1962, recorded by Blue Note Records, but then released on the fledgling ESP-Disk label, which went on to a notable career of releasing free jazz, underground rock and other cutting edge sounds. Having left Atlantic and not feeling appreciated for his utterly original approach to music, Coleman decided to use his own limited funds to rent New York's Town Hall and present a concert that took evolving ideas of composition and expression to a level beyond what he had done at Atlantic. Bernard Stollman, who founded ESP-Disk, was also Coleman's manager at the time.

He had the perfect rhythm section for his new phase in drummer Charles Moffett, whose cymbal work in particular was notable, as well as the stunning bassist David Izenzon, whose clasically-dervived bowing technique was phenomenal in addition to his pizzicato playing. On this record, there are two short pieces, "Doughnut" and "Sadness," in which these two masters utilized their individual and collective strengths to give Coleman a new palette of textures and colors from which to solo.

"Dedication to Poets and Writers," written for a string quartet played by violinists Selwart Clark and Nathan Goldstein, celloist Kermit Moore and Julian Barber on viola, was Coleman's first attempt at a notated piece along classical lines. Coleman had been involved in a project of so-called Third Stream music, blending modernist classical music with jazz, through its most noted promoter, Gunther Schuller, in which the composer wrote "Abstractions" specifically for Coleman.

Remco Takken's notes point out that Izenzon's classical training and approach to bowing on his double bass provide a bridge between the string quartet and the trio performances at this show and this listener totally agrees that what could have been disparate, jarring contrasts became more of an organic, unified program because of Izenzon's way of playing. Coleman's approach to harmolodics, which was always being refined and redeveloped, is also detectable on close listening.

"The Ark" probably represents the closest linkage between the trio and string quartet sections of the concert. A sprawling, multi-faceted, and fascinating excursion into all the tools Coleman had to offer at the time, the piece really is a stunning effort, with Coleman exploring the full range of his alto, Moffett using his highly effective and understated approach, even on his fine soloing, on the kit, highlighted by his shimmering cymbal work, and Izenzon demonstrating why he was a marvel of playing the bass in both the arco and pizzicato styles.

Coleman, however, was thoroughly demoralized by the conditions surrounding his music in terms of what he felt was a lack of appreciation as well as financial concerns and went on a self-imposed hiatus from public performance and recording that lasted two years. During 1963 and 1964, however, he worked busily on his compositional approaches through harmolodics and looked for new ways of expression through learning two new instruments. Although his technique was rough, the emotive content of his playing on trumpet and violin added new dimensions of sound, in terms of color and texture. These are, probably, best exemplified by the stunning recordings from the Golden Circle in Copenhagen from 1965, released on Blue Note.

As a document that was, simultaneously the end of an era from the big splash he made in New York in 1959 and the harbinger of a new phase that was delayed for a couple of years, Town Hall, 1962 is probably, along with a record like Colors, among the least appreciated of Coleman's half-century of recorded work.

Listening to this album tonight evokes clear recollections of the 1990 trio performance (intended to be a reunion of the 1959 quartet, but trumpeter Don Cherry had to bow out because of the flu) at the Orpheum Theater in Los Angeles during Peter Sellars' Los Angeles Festival. Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins were certainly different in their approaches as the rhythm section, but the full integration of drummer and bass player with the leader is striking in both cases.

Finally, from the perspective of remembrance, this blogger is grateful to have heard Coleman in one of his last local performances, at UCLA's Royce Hall nearly five years ago. It was typically probing, with two bassists, Coleman's son Denardo playing with great mastery on the drumkit (amazing that his father was derided for using his 10-year old son, along with the late, great Charlie Haden on bass, on 1966's The Empty Foxhole), a Japanese singer employing wordless and otherworldly vocals, and then, for a couple pieces, bassist Flea, from the Red Hot Chili Peppers but also a huge jazz fan, joining the quartet and showing that his jazz chops were substantial.

Even at 80, Coleman demonstrated his lifelong commitment to expressing, fully and freely, the wonder of sound. That may be his legacy: taking himself, his fellow musicians, and listeners on an uncharted journey into the ineffable joys of music.

Now, as "The Ark" has just ended and the applause fades, this is the time to say to Ornette Coleman, one of the great creative artists of our time, rest in peace and thank you for sharing your wonder with us.

This blogger has vivid memories of buying, in the same day in 1990, John Coltrane's My Favorite Things and an album of Atlantic outtakes from Coleman's years there, The Art of the Improvisors, especially its opening, frenetic "The Circle with a Hole in the Middle." That recording let quickly to purchases of such classics as The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century, Free Jazz and many others.

Coleman's approach to harmony, his melodic sense, and the total freedom given to the musicians to play what felt right, provided they were listening and responding to each other, was revolutionary, drawing scorn and appreciation across the spectrum.

While his influence wasn't such that covers of his pieces are very common, outside of a few iconic tracks like "Lonely Woman" or the rare tribute album, like John Zorn's amazing Spy vs. Spy, his legacy is perhaps best represented in the spirit of expression that the murkily-defined concept of harmolodics, in which harmony is given equal weight with melody in the context of free expression concerning time, rhythm and other structures, embodied.

Now, in 1990, this listener, new to jazz, did not appreciate much of these notions, but was drawn to the playful, celebratory, light and crisp sounds of those Atlantic recordings that were made at the peak of Coleman's notoriety.

Of course, Coleman continued to probe, explore and express through his years at Blue Note, Columbia and then on to his electric group, Prime Time, and more modern pursuits, including the remarkable Sound Grammar, the fantastic collaboration with Pat Metheny, Sound X, and the little-discussed duet with Joachim Kuhn, Colors, a rare instance of the use of piano in Coleman's music. That live recording in Leipzig from the mid-1990s represented Coleman's unceasing explorations in instrumentation, as well as sound, and may have had a precursor from over thirty years before.

This was the Town Hall concert of 21 December 1962, recorded by Blue Note Records, but then released on the fledgling ESP-Disk label, which went on to a notable career of releasing free jazz, underground rock and other cutting edge sounds. Having left Atlantic and not feeling appreciated for his utterly original approach to music, Coleman decided to use his own limited funds to rent New York's Town Hall and present a concert that took evolving ideas of composition and expression to a level beyond what he had done at Atlantic. Bernard Stollman, who founded ESP-Disk, was also Coleman's manager at the time.

He had the perfect rhythm section for his new phase in drummer Charles Moffett, whose cymbal work in particular was notable, as well as the stunning bassist David Izenzon, whose clasically-dervived bowing technique was phenomenal in addition to his pizzicato playing. On this record, there are two short pieces, "Doughnut" and "Sadness," in which these two masters utilized their individual and collective strengths to give Coleman a new palette of textures and colors from which to solo.

"Dedication to Poets and Writers," written for a string quartet played by violinists Selwart Clark and Nathan Goldstein, celloist Kermit Moore and Julian Barber on viola, was Coleman's first attempt at a notated piece along classical lines. Coleman had been involved in a project of so-called Third Stream music, blending modernist classical music with jazz, through its most noted promoter, Gunther Schuller, in which the composer wrote "Abstractions" specifically for Coleman.

Remco Takken's notes point out that Izenzon's classical training and approach to bowing on his double bass provide a bridge between the string quartet and the trio performances at this show and this listener totally agrees that what could have been disparate, jarring contrasts became more of an organic, unified program because of Izenzon's way of playing. Coleman's approach to harmolodics, which was always being refined and redeveloped, is also detectable on close listening.

"The Ark" probably represents the closest linkage between the trio and string quartet sections of the concert. A sprawling, multi-faceted, and fascinating excursion into all the tools Coleman had to offer at the time, the piece really is a stunning effort, with Coleman exploring the full range of his alto, Moffett using his highly effective and understated approach, even on his fine soloing, on the kit, highlighted by his shimmering cymbal work, and Izenzon demonstrating why he was a marvel of playing the bass in both the arco and pizzicato styles.