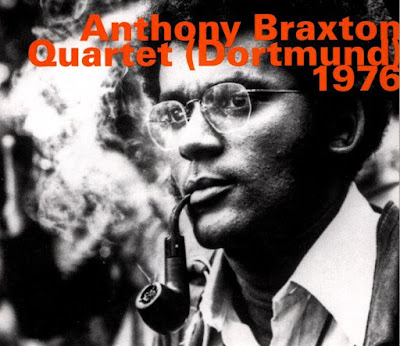

For all of the amazing music, the prolific and profound Anthony Braxton has created for more than a half-century, it is hard to find any endeavor of his that was more exciting and accomplished as the quartet that lasted just a half of a year in 1976. Featuring the remarkable rhythm section of Dave Holland on bass and Barry Altschul on drums and percussion, with the leader playing his usual array of horns (alto, contrabass, and sopranino saxes, and Eb, contrabass and standard clarinet), the additional element that powered this ensemble was the introduction of the amazing George Lewis on trombone.

This Hat Hut release is from the inaugural Dortmund Jazz Festival held in Germany on Halloween and the group, which disbanded after a show in Berlin several days later, plays at a peak of precision, passion (not something usually associated with Braxton by critics), power and, fun (also not highlighted in reviews). It helps that the group plays three versions of Composition 40, one of the most common pieces that Braxton played, and that the opener with version F is, through a Holland solo, transitioned to Composition 23J, another oft-performed work. The combined pieces take us on a stunning 26-minute journey, with a mind-blowing solo by Braxton that generates a burst of enthusisastic applause, with Lewis offering his own masterful solo after that!

Composition 40 (O) follows with some remarkable sounds, like birdcalls from Altschul and a panoply of "honks, grunts, quacks and howls" from Lewis and Braxton, "with Dave Holland tight on their tails," as expressed by Graham Lock in his thorough and enormously helpful notes. Then there is Composition 6(C) which Braxton indicated "was composed to be a circus march type of music," though by the Dortmund concert "has provided an ideal vehicle for 'collage' improvisation." This, Lock explains, means "a parade-ground melee" with the horns tossing off "marching riffs in glorious profusion." Finally, there is Composition 40(B) which, Braxton observed, "was composed with respect to the implications" of such jazz giants as Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Lennie Tristano, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy— but with Braxton's unique perspective.

It must be said that, complicated as Braxton's concepts can be, Lock does as a good a job as can be expected at explaining what's behind this whirlwind's approaches. As complex as Braxton's work is, and it can be daunting, suspending preconceptions of what jazz is supposed to be, much less other forms of music, and just letting him and his compatriots take you on their wild and wonderful journey can be highly rewarding.