In 1974, disillusioned with the direction of King Crimson, traveling on the road, and dealing with the music business, as well as feeling in a spiritual crisis, Robert Fripp disbanded the group that had just made the revelatory recording

Red. After working on a final statement in the form of the live album

U.S.A., released in 1975, Fripp stopped making music and took a ten-month course at the International Academy for Continuous Education, created by John G. Bennett as a means for studying the aim of the spiritual life based largely on the teachings of the Russian-Armenian G.I. Gurdjieff (whose music was performed by pianist Keith Jarrett, profiled in this blog, in a 1980 recording.)

Fripp then did something remarkable for someone who came up in the music world of the late 1960s, he moved to New York and immersed himself in the independent music scene there. Meantime, he was lured back into performing when Brian Eno, with whom Fripp made the innovative 1973 album

No Pussyfooting, asked him to work on some tracks for David Bowie's 1977 album,

Heroes, with Fripp's distinctive guitar providing the backbone for the title track. Fripp went on to produce an Peter Gabriel solo record, one by the folk act, The Roches, and even a solo album by Daryl Hall. Finally, Fripp created a remarkable album of his own,

Exposure, which was released in 1979 and which will be profiled here later. In 1980, Fripp resurrected the name of his first significant group, The League of Gentlemen, and teamed with XTC keyboardist Barry Andrews (later in Shriekback), Sara Lee, a bassist who later played with Gang of Four and the B-52s among others, and drummer Johnny Toobad, replaced later by Kevin Wilkinson, who subsequently was in China Crisis and Squeeze.) The band released one album and toured for much of that year before the project was terminated.

Determined not to go back to the past, Fripp then conceived of a group called Discipline. Bassist Tony Levin, who had worked on the Peter Gabriel solo record (and has been touring with him lately), impressed Fripp greatly, as had an amazing guitarist and singer, Adrian Belew, who was hired by Frank Zappa from obscurity and subsequently worked with Bowie and Talking Heads. The one link to the King Crimson past was Fripp's offer to drummer Bill Bruford to join the new quartet. After rehearsing, Discipline began playing shows and developed an immediate rapport. Soon, however, it became apparent to Fripp and the others that the new group was actually King Crimson and Discipline was jettisoned, though it would, in 1993, be resurrected as part of Fripp's independent label, Discipline Global Mobile.

The 1981 version of King Crimson bore almost no resemblance to the earlier iterations, which was one of the most remarkable aspects of it. Belew was the first guitarist to work with Fripp and his extensive use of the whammy-bar and other pyrotechnics were stunning, as well as being an excellent counterpoint to Fripp's more subdued, but complex and idiosyncratic sound. Based on a new-found interest in Balinese gamelan music, the two also developed a highly integrated cross-picking sound that made King Crimson distinctive. Levin's use of the new Chapman Stick, which is a guitar-like instrument that is able to play bass and melody lines as well as ambient like textures and thick chords, was also highly unusual and he also played the traditional bass. Finally, Bruford was asked (restricted?) by Fripp to disdain too much use of the cymbal and be more of a rhythmic accompaniment to the group and also used a new technology, an electronic drum kit by Simmons, augmented by some acoustic pieces.

The record the band issued that year,

Discipline, was not only light years removed from earlier King Crimson lineups and recordings, but was radically different from anything else of the time. It is a testament to Fripp's desire and that of his bandmates to be forward thinking in terms of sound, but it was also essential to have the rhythmic flexibility and virtuosity of Levin and Bruford, who made a fantastic team, and to have the rare combination of a staggering guitarist, a fine vocalist and good songwriter in Belew. Belew, in particular, provided a goofy humor and an engaging warmth to his other talents to make this new version of KC something different and timely.

As has been stated here before, it is hard to look at

In the Court of the Crimson King (1969),

Red (1974)

and

Discipline (1981) and choose which one is "best." They are dramatically varied from one another, but have that unifying spirit of experimentalism and adventure that marks the spirit of King Crimson. It has to be said, though, that

Discipline is more accessible and has a continuity and seamlessness that the others don't possess, although "21st Century Schizoid Man" and "Starless" are epochal recordings that stand head-and-shoulders, in this listener's opinion, above everything else the band did, excepting perhaps "Lark's Tongues in Aspic, Part 2," and a personal favorite, the fascinating "The Talking Drum," both from 1973's

Larks Tongues in Aspic.

But, "Indiscpline" is right up there. Belew's agitated soliloquy based on his wife's reaction to a work of art she created is accompanied by some fabulous instrumental accompaniment, including a guitar solo by Fripp reminiscent of the one found on "A Sailor's Tale" from 1971's

Islands, Levin's anchoring bass playing, and Bruford's rare opportunity to rove around his kit, but highlighted by his beautifully tight roll just before Belew tears into his distinctive solo.

"Elephant Talk" has a cool lyrical format, in which Belew spouts out words from each of the letters from A to, you got it, E--he has a knack for clever lyrical conceits that break down some of the heaviness of the KC sound and Fripp's processed "mouse" solo is fascinating. "Frame by Frame" has a nice soaring vocal by Belew with backing vocals from Levin, something not found in previous versions of the band.

"Thela Hun Gingeet" is an anagram for "Heat in the Jungle" with another unusual compositional element--during rehearsals, Belew explained his idea to the band about what the song was about, the hardness of an urban street environment, when Fripp suggested he take his portable tape recorded and go out into the street and record what was there. Belew was then actually set upon by some men who thought he was an undercover cop with the singer/vocalist protesting that he was in a band recording an album and that he was on the street for that reason. Somehow, the men decided to walk away only to have Belew run into a police officer. Returning to the studio and visible shaken and upset, Belew retold the incident to his fellow band members, but Fripp had the presence of mind to ask the recording engineer to tape what Belew related. This was added to the song to give it a disconcerting element of unreality--though, at first listen, it seemed to this blogger to be contrived, though still effective as a vocal device.

Aside from "Indiscipline" the other highlight is the gorgeous "Matte Kudasai," for which Fripp had a previously-existing guitar line, but it is Belew's vocal that stands out. Later incarnations of the group would come up with such Belew signatures as "One Time" and "Eyes Wide Open." While fans of the older versions of KC would point to "I Talk to the Wind," "Cadence and Cascade" and others as being emblematic of the balladic aspect of the group, "Matte Kudasai" is both beautiful, but less baroque.

Discipline concludes with two instrumentals, the evocative "The Sheltering Sky" and "Discipline," which features that complex, interwoven, cross-picking playing by Fripp and Belew mentioned above. In all, this album is a striking, original and daring leap to a modern sound that most 1960s era bands and performers could not conceive of trying. It is notable that John Wetton, whose powerful and nimble bass playing and smoky vocals on the classic 1972-74 KC lineup, became a pop rock phenomenon with Asia just a year later. The differences of where he went (albeit leading to great riches, if not longevity) compared to where Fripp headed are telling.

An early CD version of the album, in 1989, as with all of those made at the time, was heralded as "definitive." Of course, this was not so, and a 30th anniversary disc came out about a decade later in 2001. Then, with further technological advances, came the 40th anniversary version in various formats (including 5.1 DTS Digital Surround, MLP Lossless and PCM Stereo) and with some bonus material. Produced and mixed by Fripp and Steven Wilson of The Porcupine Tree who has overseen most of the reissued 40th anniversary material, the sound is excellent.

The Eighties version of Crimson released two more albums, the underrated

Beat (1982) and

Three of a Perfect Pair (1984) and, after the excellence of

Discipline, it was probably unfair to ask the band to come near to reaching that level. This listener first heard the band in spring 1984 when a friend wanted to see KC play at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles. After curtly declining in some disdain, visions of prog excess (side-long suites about court jesters, dancing in the sun, and Tarkus, etc.) roiling about in the brain, the friend asked for a listen to a few Crimson records to demonstrate that they were different. Indeed they were--a run through

ITCOTCK,

Starless and Bible Black,

Red and, most strikingly,

Discipline clearly showed this.

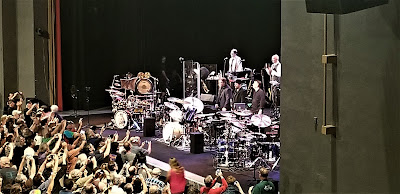

The June concert was amazing. The tall, balding Levin providing a notable presence aside from his unbelievable playing, Bruford expertly laying down electronic and analog rhythms, Belew crooning, elephant talking, and whammy-bar wailing his way into the audience's hearts, and Fripp, as always, calmly seated at the side and playing off the various strengths of his fellow band members and himself. A month or so later, it was over as Fripp decided to walk away from Crimson once again.

For this listener, the budding interest in the band ended--it was an unexpected detour from the alternative rock that ruled the roost. In 1994, the

VROOOM CD was picked up out of sheer curiosity and, though it was intriguing, nothing further came of it. Then, in 2009, a nagging question about whether Crimson would still be of interest (

Starless and Bible Black, in particular, kept popping into the cranium) led to a hesitant purchase of

Larks Tongues in Aspic and it was "The Talking Drum" that did it. Since then, it has been a near-continuous exploration of all things Crimson and Fripp, though the news that the grand plans for the 40th anniversary year ground to a halt followed by Fripp's "retirement" was disappointing.

Suddenly, with a long-standing dispute over royalties with Universal Music Group and other difficulties resolved, this September Fripp announced another version of Crimson would be "in service" by that time in 2014. The news was tempered some by the revelation that Belew was not invited and the vocalist would be Jakko Jakszyk, who performed on a recent KC "projekct" with Fripp, Mel Collins from the 1970-72 KC era, Gavin Harrison (of The Porcupine Tree and the short 2008 Crimson mini-tour). The "projekct" has been defined as a sort of "research and development" aspect of portions of the larger Crim to move to the next phase.

Now that the five men who worked on

A Scarcity of Miracles are in the new lineup along with

two other drummers, KC vet Pat Mastelotto and Bill Rieflin, formerly of Ministry and REM and who has worked with Fripp on other projects, including The Humans, the band of Fripp's wife Toyah Willcox, it will be interesting to see what new directions will come of it. Undoubtedly, much of the attention will be focused on Jakszyk, who will, fairly or not, be compared to Greg Lake, John Wetton and Adrian Belew.

Whatever happens, it is sure to be interesting and unexpected and nothing less can be expected from the iconoclastic, enigmatic, but remarkably and resiliently creative Robert Fripp.