Christian Wolff, who is still among us as he approaches his 87th birthday, has survived all of his compatriots in the so-called New York School of experimental composers centered around John Cage and his theories and approaches to sound and including Morton Feldman, Earle Brown and David Tudor. The exploration of the possibilities of expression of sound through prepared instrumentation, the use of indeterminacy and chance operations (using, for example, the I Ching to determine what to play next), and other aspects, can be understandably off-putting, though, with an open mind and ears, the ride can be quite intriguing and fascinating.

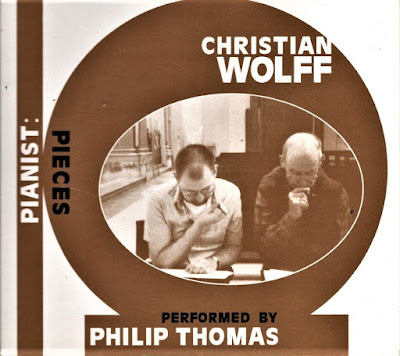

An example is the three-disc set issued by the Belgian label Sub Rosa called Pianist: Pieces and which provides the dramatic contrast between Wolff's early work during the 1950s heyday of the New York School and a slew of pieces issued between 2000 and 2010 after he retired from teaching from Dartmouth. Perfomer Philip Thomas provided very useful and interesting notes, observing, for example, that Cage felt that Wolff was the most musical of the group and Thomas outlines how the experimentation and pedigree of musicality through Ives, Webern, Bach, Schumann, Hayden and others can be discerned in the music.

Most helpful is Thomas' evocation of how Wolff utilized discontinuity, silences, isolated and fragmented sounds and indeterminacy of notation. This latter involves indications of which fingers to use, but not which notes; unspecified duration of notes; playing notes in any octave or clef; leaving out instructions for tempo, articulation and dynamics and the "wedge," or a pause or breath of any length. This allows tremendous freedom, along with significant challenges for the player in working towards a "meeting point" with the composer. Thomas stated that the experiences of working with Wolff's work "provoke me to play in ways I would not ordinarily consider."

For the listener, at least this one, this also is the case, in that listening to experimentalists like Wolff leads to new ways of hearing music, though none of this is anywhere nearly as shocking and unnerving as it was to those confronting such approaches to sound back in the Fifties. It is also apt that, when the set was burned to my computer, the pieces were not arranged in the order by disc, but, rather so that the three track 1s are followed by the three track 2s and so on. This discontinuity and a sort of indeterminacy seems more than fitting and does not, in the least, affect the enjoyment of hearing Wolff's particularized approaches to composing for the piano.

No comments:

Post a Comment