Anthony Braxton, recently honored as a NEA Jazz Master, has had his music stereotyped as cerebral, dense, impenetrable and more. The difficulty probably stems largely from the fact that he follows his vision for sound in ways that don't easily dovetail into neat categorizations about what separates improvised jazz from notated composition and that he puts such a great deal of thought into what he creates that his music doesn't provide easy benchmarks from which to listen. Braxton's music does take effort, more than most people would want to (which is obviously just fine), but the rewards, at least for this listener, are palpable and long-lasting.

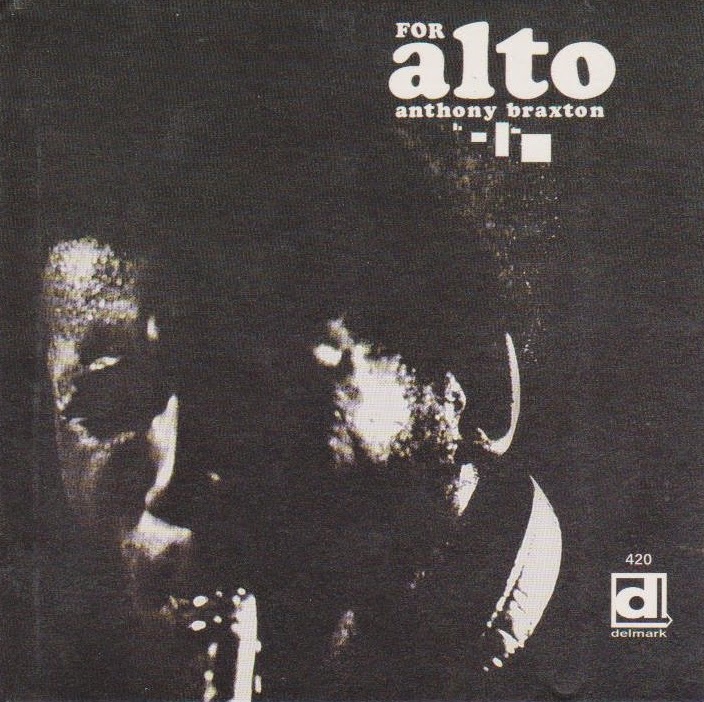

There are times, however, when his music has more approachability than others and, while it might be thought that a double album of solo saxophone would be the last place to approach approachability, For Alto actually has a lot that can appeal more broadly than Braxton's debut record, 3 Compositions of New Jazz, which was highly complex, ambient and "difficult."

Still, this is Anthony Braxton, so there are plenty of moments of knotty abstraction, but there are also many instances in which he plays quite melodically, soulfully and with a passion that is, to these ears, accessible, if a listener takes that great advice from saxophonist Albert Ayler and his trumpeter brother, Donald, to "follow the sound" rather than the notes.

After a brief and relatively placid forty-five second opener, the altoist tears into the next track, dedicated to composer John Cage. Though it is nine minutes long, a concentrated listening to the way that Braxton develops his solo, from the very fast and aggressive first third to a quieter, if still quite intricate, following section that then goes into a remarkable section of overblowing at the upper register after about 4:30 and then carrying the piece through to the end, it is easy to get caught up in Braxton's sheer inspired passion for what he was doing.

By contrast, the third piece, dedicated to artist Murray De Pillars, is, at first, more melodic and drenched with soulfulness, demonstrating that Braxton could play with a simplified emotion, while still tackling complex structures, such as a notable array of trills, in very effective ways. Then, he turns to some harsher sounds, alternating between mid and upper range blowing and then punctuated with harsh honks that are very interesting.

A smooth segue into a track dedicated to the great pianist Cecil Taylor moves the tempo up, but not as frenetically as the Cage piece. Again, Braxton is a marvel in terms of his mixture of formidable technique and the sheer joy of expression. While it would be tempting to try to equate the saxophonist's approach on this piece of Taylor's ways of playing the piano, it is almost certainly more plausible to think of the spirit of exploration to be the linkage. In fact, towards the end the playing gets quite bluesy. In any case, it is great to have one intrepid explorer saluting another.

The longest track, at nearly thirteen minutes, is dedicated to Ann and Peter Allen and the piece is very ambient, understated and the silences or near-silences are notable given much of the busy playing that came before. The beauty of this piece and in much of the ten-minute one that follows, dedicated to Susan Axelrod, is that Braxton provides the opportunity for ample space in terms of varieties of sound that he works with. The altoist does open up more with the Axelrod work, turning up the volume, increasing the tempo and playing with more blues feeling, while keeping a strong melodic current going.

It makes the album much more interesting and compelling when he sequenced the tracks to give the listener a chance to enjoy a full range of emotion and sound, from hard-charging, complex runs and blasts of intensity to the more introspective and moodier elements, as found in the Allen and Axelrod pieces.

In fact, the ten-minute piece dedicated to friend Kenny McKenny moves into very experimental territory with multiphonics, unusual breathing and fingering technique and other technical displays that are very much contrasting with the two works before. Again, though, for those willing to go on that journey into new territory, it is fascinating being in "the bubble" with Braxton as he explores ways to play the saxophone that are probably the most innovative after the death of John Coltrane two years before. Still, it could easily be understood why the McKenny piece could prove difficult to many listeners and play right into the stereotype mentioned at the outset.

Fittingly, the album concludes with a nearly twenty minute work dedicated to Leroy Jenkins, who worked with Braxton on the 3 Compositions of New Jazz record and subsequent albums recorded for the Actuel label in France and others. The piece starts off quietly and slowly, with repetitive patterns dominating and then punctuated with more honks and odd blasts of sound to contrast.

Braxton was only 24 when this album was recorded, but it sounds the summation of years of careful accumulation of sounds developed in live and recorded situations by someone much further along in years. It also bears remembering that this was 1969 when jazz was largely dominated by psychedelic and spiritual music, much of it fantastic, by such major figures as Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders and with Miles Davis's electric revolution just around the corner (yes, not quite "On the Corner".)

Whereas the work of Mrs. Coltrane or Sanders or Davis definitely sounds "of the time," For Alto has a timeless quality to it. Obviously, being a solo album makes it easier (without harps or electric keyboards or the blissed-out vocals common to the period). But, it's also that listening to this album makes the listener feel that it's just you and the alto player as he bares his soul through a dizzying palette of sounds that probably was not thought possible at the time.

For Alto was audacious then and now, over 70 minutes of solo alto saxophone playing by a young man already determined to rewrite the rules of not just playing his instrument, but of composing and of working with sound. Forty-five years later, the album still sounds ground-breaking, hugely ambitious, fully immersive and impressively realized.

If the NEA Jazz Master program had existed 45 years ago, it seems plausible that Braxton could have been given the award just on the basis of this fantastic and essential document. In any case, it was great to see him get the honor this late in his life and finally receive some belated recognition for his immense, if somewhat challenging, body of work.

No comments:

Post a Comment